Do Just Enough Documentation

Documentation can consume a significant amount of a program’s schedule. To accelerate a program, the team must constrain the amount of time spent developing, reviewing, and approving documents. The GAO reported in GAO-15-192, acquisition programs spent over 2 years on average completing numerous information requirements for their most recent milestone decision, yet acquisition officials considered only about half of the requirements as high value. The requirements, in total, averaged 5,600 staff days to document.

The following three principles can help enable constraints:

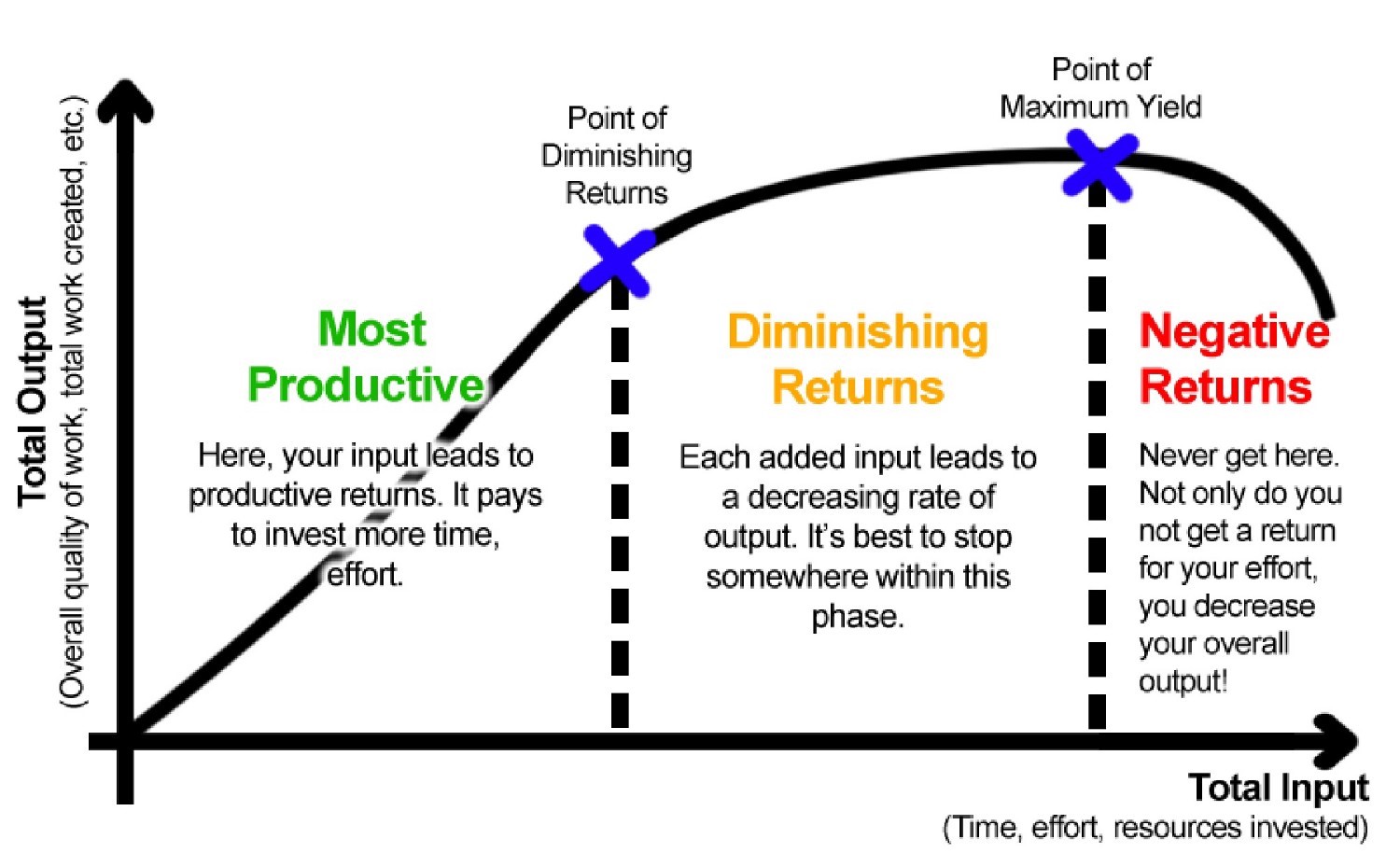

- The Pareto Principle: 80% of the results comes from 20% of the effort. Therefore, focus on documenting the most valuable elements of the program’s strategy.

- The Minimum Effective Dose (MED): Medical professionals recommend patients take the least amount of medicine that delivers the desired effect. Similarly, write “as little as possible, as much as necessary.”

- The Agile Manifesto: The Agile software approach emphasizes working software over comprehensive documentation, and offers this perspective: “Simplicity–the art of maximizing the amount of work not done–is essential.”

An acceleration team should thus aim to only produce the documents that are useful and needed to manage the program, rather than writing “compliance only” documents which exist only to satisfy the interests of an outside stakeholder.

The Air Force’s Business and Enterprise Systems Product Innovation (BESPIN) program won the 2019 AFLCMC Acquisition Management Award Golden Scissors Award for the most creative tailoring in a 5000.02 program.

The Section 809 Panel recommended eliminating redundant documentation requirements or superfluous approvals when appropriate consideration is given and documented as part of acquisition planning.

Recommendation 74 achieves at least two goals: it streamlines acquisition processes, and it allows contracting officers to spend more time on customer support. This recommendation was developed by contracting officers from each military service who were motivated to find solutions for duplicative requirements that routinely frustrate them and unnecessarily slow down the contracting process. Some of the changes called for in Recommendation 74 can be done today, such as combining the acquisition strategy and acquisition plan. But culture has not let this consolidation become the normal course of business.

DoD can help change the culture immediately by implementing a major piece of Recommendation 74 by consolidating Acquisition Strategies, Acquisition Plans, and other documentation into one document. DoD should then issue guidance that Acquisition Strategies and Acquisition Plans shall be one document and will include other higher level approval documents, such as justification for single award >$112m IDIQ contracts and justification for use of an incentive or award fee contract. Once this guidance is released, a memorandum should be issued making this consolidation a “shall” and requiring a waiver be approved by GO or SES if not used.

Source: Larry Asch, Section 809 Panel staff, via NPS Acquisition Research Program Newsletter

Actions You Can Take

-

Define Just Enough. Identify what “information” is required by law and by policies (at which level of the organization) as well as additional documentation is commonly required. Note: There may be a law that requires a program to provide X information, yet agency headquarters staff have interpreted that to be complete a large document per their template or standards.

List The Minimum Set Identify the minimum set of documents that can capture the required information. Keep in mind that a functional oversight organization may traditionally expect a functional document. A program office may merge the content of that document with others to minimize the number of documents to coordinate. It also provides each oversight staff the ability to see the bigger picture when reviewing their area. However it opens up the risk that that oversight staff then provide comments on areas of the larger document beyond their functional domain. -

Propose Tailored Approach. If there are requirements in policy that don’t make sense for your program, identify them and offer recommendations to tailor or waive that requirement. Be sure to include the information on the waiver authority (organization, duty title, etc).

-

Focus on Relevance more than Compliance. Understand the difference between a requirement that a program must have an XYZ strategy which complies with an organization’s template vs a requirement that a program capture and convey the core elements of their strategy to decision authorities and stakeholders. Ultimately the documentation is designed to ensure the program office has done sufficient critical thinking to execute the next phase of the program.

-

Match Plans With Requirements. Develop an outline of the documentation the program office plans to compile, with the intended content in each document. Identify how this proposed set meets the documentation requirements.

-

Get Buy-In Early. Present the proposed documentation outline with the decision authorities EARLY in the process to solicit their approval. As some functional oversight organizations may resist tailoring their functional document, this may require the program’s leadership chain (assuming they agree with the approach) to engage on this is how we need to move forward for the program.

-

Assign Responsibility. Identify leads responsible for each document, who maintain the “gold copy”, work with a team to collaboratively iterate on the document, and keep all required stakeholders updated on the content and progress.

References

- Please Tailor Your Acquisition Strategy!, Brian Schultz

- Why Lengthy Business Plans Increase The Risk Of Failure, Alexander Osterwalder

- The 9-Word NDA, Dan Ward

- Experiments In Doing Less, Dan Ward

- Simplify Your Strategy, Pete Modigliani

- The Need for Agile Program Documentation, LTC TJ Wright

- GAO Report 15-192 on DoD Decision Making

- DOD Acquisition Streamlining (NPS Capstone Project), Jennifer Echard, Jeffrey Harris, Karen Richey

In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.