Should-Cost Management

This page is MITRE authored content curated from many DoD sources.

Should-Cost Management (SCM) is a program management process for DoD acquisition programs that establishes cost reduction goals for an acquisition program through its lifecycle. SCM helps program management identify and eliminate inefficient and non-productive tasks that drive costs in their programs. It’s designed to proactively target cost reduction and improve productivity. SCM is required for all ACAT designated programs where acquisition executives are responsible for approving targets and monitoring progress at program milestones.

“Should-Cost Management, the idea that acquisition managers should exploit every opportunity to squeeze unnecessary and unproductive costs out of their programs rather than assuming that the cost and schedule overruns that have plagued defense programs for years are an immutable characteristic of defense acquisition. The basic philosophy here was that we should not just accept the independent cost estimates as a self-fulfilling prophesy and assume that we’d spend to those levels. We should look at opportunities to reduce cost well ahead of time, and I think that idea has gotten across to the workforce now. It took a long time, but I think we’ve gotten a lot of success with that.”

Current Policies and Procedures

The concept of a should-cost analysis comes from industrial engineering which focuses on the manufacturing process and the optimization of complex processes, systems or organizations. In government acquisition, should-cost review is documented as a specialized form of cost analysis as defined in FAR 15.407-4 and DFARS 215.407-4. The intent of the FAR and DFAR definitions is to direct the contracting community to request should-cost reviews to better understand the costs associated with manufacturing process (both direct and indirect) prior to production decisions and contract awards, to ensure that the government is paying for the most economical and efficient manufacturing process it can for its weapon systems, which are often contracted in a sole source environment.

With the implementation of Under Secretary of the Defense Department/Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (USD(AT&L)) Better Buying Power (BBP) Initiatives in 2010, DoD policy expands the FAR’s Should-Cost Review definition, which was historically used for production contract negotiations, to a program management process which consistently strives to find and execute savings opportunities across a program’s life-cycle with the goal of increasing purchasing power.

Should-cost management is not limited to just the production phase of a program – the government must apply a “cradle-to-grave” should-cost approach by continuously looking for cost saving opportunities in both development and sustainment.

“Embracing the ‘Should-Cost’ management paradigm represents a cultural change, not just a one-time event.”

– Dr. Ashton Carter and John Mueller

Over the last six years, DoD continues to refine the policies and procedures related to Should-Cost Management following with BBP 2.0, BBP 3.0 and multiple USD(AT&L) Implementation Directives including Better Buying Power – Obtaining Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending; the Joint Memorandum on Savings Related to Should-Cost and USD AT&L’s Memo on Implementation of Should-Cost and Will-Cost Management, just to name a few. Today, SCM has evolved into a well-defined program management requirement for all ACAT designated programs within the DoD acquisition management process. Prior to conducting a should-cost analysis, program managers should review all DoD policies and procedures, specifically the should-cost references that are included in multiple sections of DoDI 5000.02 Change 3, dated August 10, 2017 which are highlighted below:

- Table 2: The Milestone and Phase Information Requirements

- Enclosure 2: Program Management: Cost Baseline Control and Use of Should-Cost Management

- Enclosure 6: Life-Cycle Sustainment: Employ a should-cost management and analysis approach to identify and implement system and enterprise sustainment cost reduction initiatives.

There is also additional guidance from the DoD Services in the form of policy instruction and handbooks.

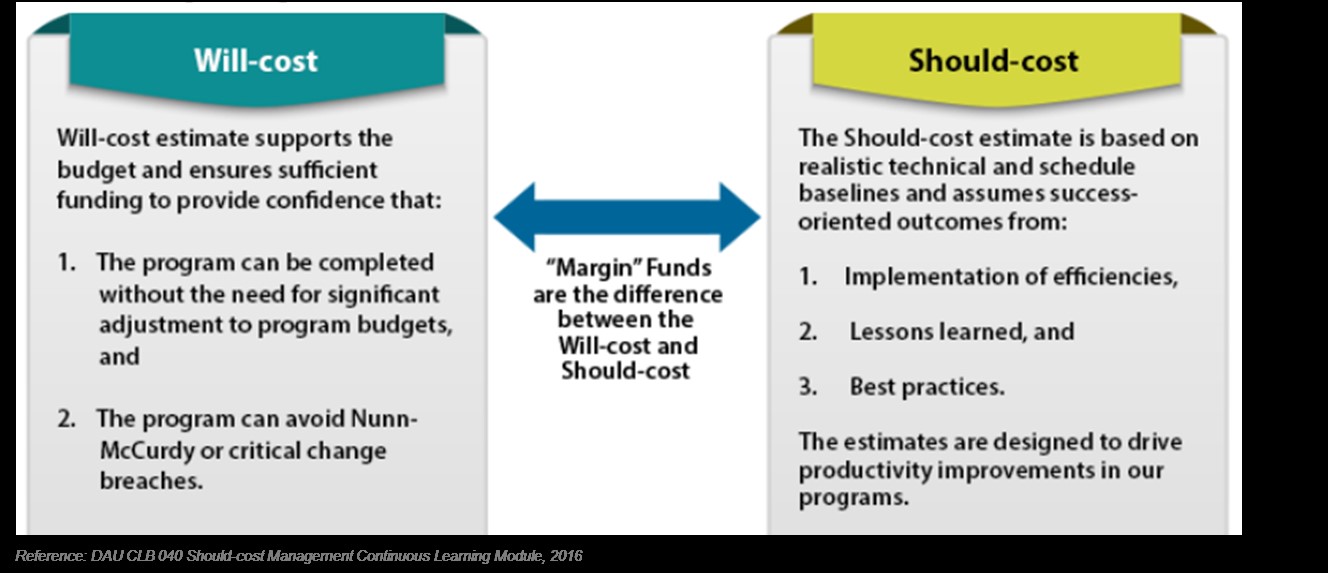

Implementing Should Cost Management

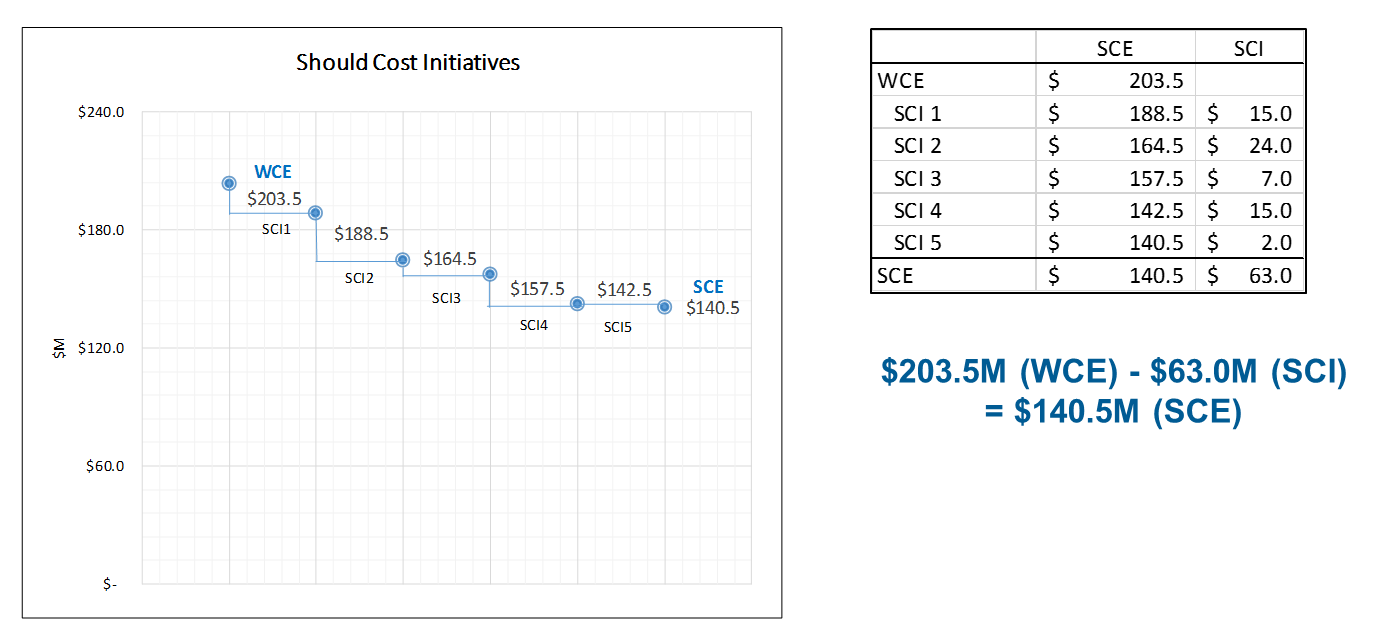

Should-Cost Management (SCM) establishes discrete, and actionable savings measures designed to reduce program costs. Program management, contracting, cost analysis, systems engineering, and logistics are critical capabilities required on a SCM team. In SCM, program management continuously analyzes specific program activities using the Independent Cost Estimate (ICE), also called the Will-Cost Estimate (WCE) as the baseline. These measures are called “Should-Cost Initiatives” (SCI) and are developed by analyzing cost-benefit considerations, associated risks and accepting those SCIs that do not reduce the value received. SCIs are a set of “tangible and executable” program initiatives which reduce costs below the WCE, or program budget, to form the program’s “Should-Cost” Estimate (SCE). The WCE remains the budget baseline for should-cost excursions and is used in internal program execution; the SCE represents what the program manager believes the program ought to cost if identified cost savings are achieved. When Should-Cost initiatives are implemented, a lower program baseline is set. “Margin Funds” is the difference between the WCE and the SCE and these funds can be reallocated for other unfunded program or portfolio requirements, therefore increasing the government’s buying power.

DoD ACAT I-III programs are required to document their SCM process at each milestone review and demonstrate that they have established realistic and actionable SCIs targets. SCI targets are approved by the Milestone Decision Authority (MDA). A robust SCM process provides program management with an internal management tool to incentivize performance to targets that help to lower costs throughout a program lifecycle. By better understanding ways we can target savings in our programs, the government can establish better negotiating positions which will result in actual costs falling below the budged ICE.

Below is a list of program management key considerations when establishing a SCM process and SCIs targets in their program (Source: AFLCMC Perspectives on Will Cost/Should Cost Management, Janice Burke (AFLCMC/FZC), Scott DeBanto (AFLCMC/AZF), 25 Mar 14):

- Should-Cost Initiatives are “tangible”, success-oriented outcomes through the implementation of efficiencies, lessons learned, and best practices

- Should-Cost does not mean trading away the long-term value for short-term gain

- Should-Cost processes and methodology can be tailored specifically for individual programs based on their own process and acquisition considerations

- SCE is based on realistic technical and schedule baselines reflected in the WCE

- Opportunities for cost savings is a process reviewed at every phase of the program’s life cycle – review both government and contractor costs objectively

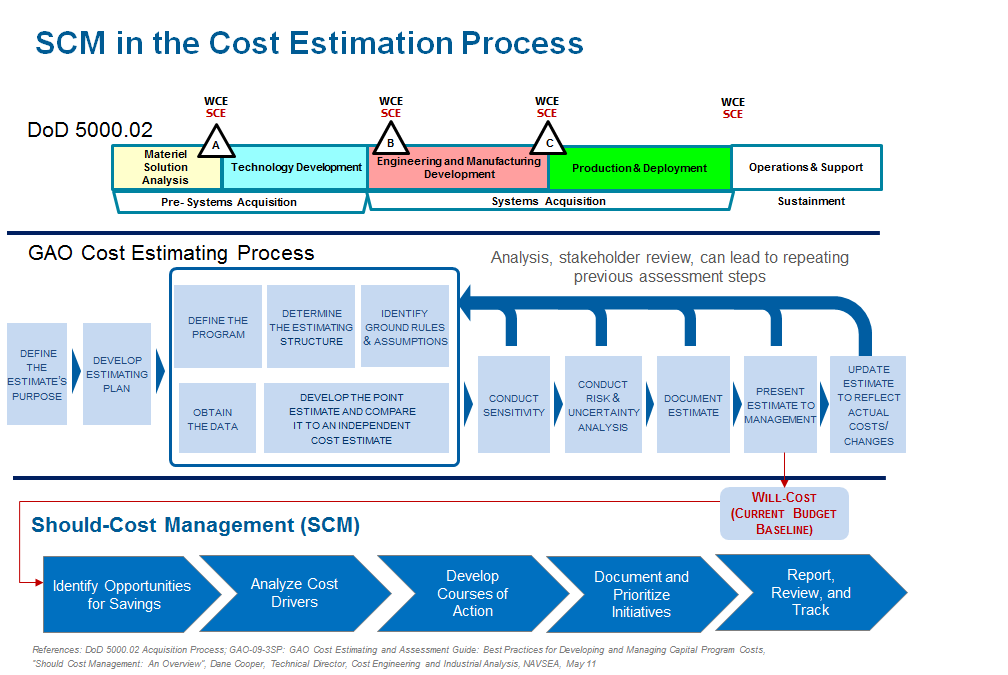

Should Cost Management in the Cost Estimation Process

The implementation of SCM is one of the cornerstones of the DoD’s BBP Initiatives and has become an integral process in the program management of acquisition programs within DoD 5000.02. As SCIs are established, the discipline of cost analysis becomes critical in quantifying potential program savings and optimizing funding. The SCM process is captured below and provides a framework of how SCM fits into DoDI 5000.02, the GAO cost estimating process, and the Should-Cost Management Methodology as defined by the Defense Acquisition University (DAU).

Will Cost vs Should Cost

|

Will-Cost |

Should-Cost |

|

Status Quo |

Challenges Status Quo |

|

Reasonable Extrapolation |

Drive Productivity |

|

Emphasis on the Past… Historical Data, Assumptions, and Lessons Learned |

Emphasis on the Future… Our past is an “economically inefficient operation” |

| Established Program’s Funding Levels

based on Independent Government Cost Estimate (IGCE) |

Establishes Affordability Targets IGCE (WCE) less SCIs=SC |

|

Established level of technical, schedule, and program risk (50% < CL < 80% ) |

Implementation of efficiencies, lessons learned, and best practices |

|

Will-Cost becomes “the floor” for which costs escalate |

Should-Cost is the “ceiling” below which costs are contained |

|

Threshold for budgeting APB, SAR, Nunn-McCurdy |

Target for program management baseline execution and contract negotiation |

|

Repeatable past performance and behavior |

Challenges past performance and seeks to change behavior |

|

Savings opportunities are not baselined |

Opportunities for program efficiencies are baselined |

|

Primarily a “Government Only” Activity |

Emphasizes collaboration and partnership with Industry |

|

Often compromises requirements to reduce cost growth |

Embraces new technologies without compromising requirements |

| Accepts program cost elements based on history |

Scrutinizes Program Cost Elements for efficiencies and savings opportunities |

Developing Should Cost Estimates

The development of Should-Cost estimates challenges the acquisition community to better understand the technical baseline and assumptions of their program which are reflected in the governments cost estimates. The DAU has outlined SCM process in DAU CLB 040 Should-cost Management Continuous Learning Module, 2016.

The program manager works with its Integrated Product Team (IPT), which includes the contractor and stakeholders to establish SCIs for their program. Each SCI is discretely estimated and represents a discrete reduction from the WCE in the form of actionable items. Should-Cost estimates can be developed using different cost estimating techniques based on the SCI being estimated such as engineering assessments, bottom-up, analogies, parametric, and actuals. The savings from each SCI is summed together for total should-cost savings phased by fiscal year. Should-cost savings is subtracted from the WCE to get the should-cost estimate target for program execution. The figure below demonstrates the relationship between the WCE and the SCE for an acquisition program.

Opportunities for Cost Savings

There are many opportunities for programs to reduce cost. The following is a list collected from multiple sources, lessons learned, success stories as well as Dr. Carter’s “10 Ingredients of Should Cost Management” found in USD(ATL)’s Implementation Memo of Will Cost and Should Cost Management” from 2011.

Program Management

- Find and benchmark analogous government and commercial programs with same contractor and facilities to compare assumptions

- Are the requirements still valid?

- Can we reduce government activities, processes, or bureaucracy that drive costs?

- Are the program’s contractor and government organizations structured and resourced properly?

- Identify fragmented, overlapped, or duplicated tasks to eliminated redundant work between the Gov’t and contractor

- Train/engage IPT and stakeholders to look for savings opportunities

- Question historical assumptions

- Reduce data and deliverables the government doesn’t need

- Active monitoring and engagement of contractor performance, requirements, and cost drivers

Contracting

- Simplify the contracting processes and documentation

- Look for competitive opportunities within a sole source environment

- Leverage existing contracts for the same product or services

- Clarify which contracting office is responsible for each requirement/contract

- Share risk with contractors if it benefits the Government

- Partner and incentive contractors to find savings and increase productivity

- Develop strategic sourcing opportunities

- Streamline deliverables by reducing unused data requirements

Cost/Schedule

- Scrutinize every element of program including contractor proposals and WCE

- Review and challenge contractor indirect rates

- Track and analyze recent program cost, schedule, and performance trends and find ways to reverse negative trends

- Scrutinize locations of work and opportunities to work at lower cost facilities

- Streamline and reduced schedule

- Analyze and understand subcontractor roles and prime contractor sub management activities (eliminated unnecessary pass-through costs)

- Leverage learning curves and minimize production breaks

Engineering/Logistics

- Have deep technical knowledge to understand the cost/performance trade space

- Review contractor’s skill mix to meet requirements and work efforts

- Explore alternative technologies or processes to reduce costs over the lifecycle

- Establish a Modular Open Systems Architecture to avoid vendor lock and integrate new subsystems

- Consolidate sustainment requirements and contracts within and across programs

- Promote supply chain management to encourage competition and incentive cost performance at lower supplier tiers

- Take advantage of integrated development & operational testing

- Leverage modeling and simulation early in design and later in testing

- Optimize the use of Government test personnel and facilities

- Government Furnished Equipment (GFE) vs Contractor Furnished Equipment (CFE)

- Develop Supplier Incentive Programs

- Strongly consider performance based logistics in support contract relationships

FAR and DFARS

The FAR 15.407-4 includes language on Should Cost Reviews

(a) General.

(1) Should-cost reviews are a specialized form of cost analysis. Should-cost reviews differ from traditional evaluation methods because they do not assume that a contractor’s historical costs reflect efficient and economical operation. Instead, these reviews evaluate the economy and efficiency of the contractor’s existing work force, methods, materials, equipment, real property, operating systems, and management. These reviews are accomplished by a multi-functional team of Government contracting, contract administration, pricing, audit, and engineering representatives. The objective of should-cost reviews is to promote both short and long-range improvements in the contractor’s economy and efficiency in order to reduce the cost of performance of Government contracts. In addition, by providing rationale for any recommendations and quantifying their impact on cost, the Government will be better able to develop realistic objectives for negotiation.

(2) There are two types of should-cost reviews — program should-cost review (see paragraph (b) of this subsection) and overhead should-cost review (see paragraph (c) of this subsection). These should-cost reviews may be performed together or independently. The scope of a should-cost review can range from a large-scale review examining the contractor’s entire operation (including plant-wide overhead and selected major subcontractors) to a small-scale tailored review examining specific portions of a contractor’s operation.

(b) Program should-cost review.

(1) A program should-cost review is used to evaluate significant elements of direct costs, such as material and labor, and associated indirect costs, usually associated with the production of major systems. When a program should-cost review is conducted relative to a contractor proposal, a separate audit report on the proposal is required.

(2) A program should-cost review should be considered, particularly in the case of a major system acquisition (see Part 34), when —

- (i) Some initial production has already taken place;

- (ii) The contract will be awarded on a sole source basis;

- (iii) There are future year production requirements for substantial quantities of like items;

- (iv) The items being acquired have a history of increasing costs;

- (v) The work is sufficiently defined to permit an effective analysis and major changes are unlikely;

- (vi) Sufficient time is available to plan and adequately conduct the should-cost review; and

- (vii) Personnel with the required skills are available or can be assigned for the duration of the should-cost review.

(3) The contracting officer should decide which elements of the contractor’s operation have the greatest potential for cost savings and assign the available personnel resources accordingly. The expertise of on-site Government personnel should be used, when appropriate. While the particular elements to be analyzed are a function of the contract work task, elements such as manufacturing, pricing and accounting, management and organization, and subcontract and vendor management are normally reviewed in a should-cost review.

(4) In acquisitions for which a program should-cost review is conducted, a separate program should-cost review team report, prepared in accordance with agency procedures, is required. The contracting officer shall consider the findings and recommendations contained in the program should-cost review team report when negotiating the contract price. After completing the negotiation, the contracting officer shall provide the ACO a report of any identified uneconomical or inefficient practices, together with a report of correction or disposition agreements reached with the contractor. The contracting officer shall establish a follow-up plan to monitor the correction of the uneconomical or inefficient practices.

(5) When a program should-cost review is planned, the contracting officer should state this fact in the acquisition plan or acquisition plan updates (see Subpart 7.1) and in the solicitation.

(c) Overhead should-cost review.

(1) An overhead should-cost review is used to evaluate indirect costs, such as fringe benefits, shipping and receiving, real property and equipment, depreciation, plant maintenance and security, taxes, and general and administrative activities. It is normally used to evaluate and negotiate an FPRA with the contractor. When an overhead should-cost review is conducted, a separate audit report is required.

(2) The following factors should be considered when selecting contractor sites for overhead should-cost reviews:

- (i) Dollar amount of Government business.

- (ii) Level of Government participation.

- (iii) Level of noncompetitive Government contracts.

- (iv) Volume of proposal activity.

- (v) Major system or program.

- (vi) Corporate reorganizations, mergers, acquisitions, or takeovers.

- (vii) Other conditions (e.g., changes in accounting systems, management, or business activity).

(3) The objective of the overhead should-cost review is to evaluate significant indirect cost elements in-depth, and identify and recommend corrective actions regarding inefficient and uneconomical practices. If it is conducted in conjunction with a program should-cost review, a separate overhead should-cost review report is not required. However, the findings and recommendations of the overhead should-cost team, or any separate overhead should-cost review report, shall be provided to the ACO. The ACO should use this information to form the basis for the Government position in negotiating an FPRA with the contractor. The ACO shall establish a follow-up plan to monitor the correction of the uneconomical or inefficient practices.

The DFARS has similar Should Cost Review language in 215.407-4

(b) Program should-cost review.

(2) DoD contracting activities should consider performing a program should-cost review before award of a definitive contract for a major system as defined by DoDI 5000.2. See DoDI 5000.2 regarding industry participation.

(c) Overhead should-cost review.

(1) Contact the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) (http://www.dcma.mil/) for questions on overhead should-cost analysis.

(2)(A) DCMA or the military department responsible for performing contract administration functions (e.g., Navy SUPSHIP) should consider, based on risk assessment, performing an overhead should-cost review of a contractor business unit (as defined in FAR 2.101) when all of the following conditions exist:

(1) Projected annual sales to DoD exceed $1 billion;

(2) Projected DoD versus total business exceeds 30 percent;

(3) Level of sole-source DoD contracts is high;

(4) Significant volume of proposal activity is anticipated;

(5) Production or development of a major weapon system or program is anticipated; and

(6) Contractor cost control/reduction initiatives appear inadequate.

(B) The head of the contracting activity may request an overhead should-cost review for a business unit that does not meet the criteria in paragraph (c)(2)(A) of this subsection.

(C) Overhead should-cost reviews are labor intensive. These reviews generally involve participation by the contracting, contract administration, and contract audit elements. The extent of availability of military department, contract administration, and contract audit resources to support DCMA-led teams should be considered when determining whether a review will be conducted. Overhead should-cost reviews generally should not be conducted at a contractor business segment more frequently than every 3 years.

GAO Assessment of Should Cost

The GAO’s 2016 Assessment of Selected Weapons Programs outlined significant progress made by DoD in Should-Cost Management since its initial inception in 2011.

“Of the 43 current programs we assessed, 39 have conducted a “should-cost” analysis resulting in anticipated savings of over $35 billion; approximately $21 billion of these savings have been realized to date.”

- DoD’s BBP initiatives emphasize the importance of driving cost improvements during contract negotiation and program execution to control costs both in the short-term and throughout the product life cycle. In accordance with DODI 5000.02, each program must conduct a “should-cost” analysis resulting in an estimate to be used as a management tool to control and reduce cost. “Should-cost” analysis can be used to justify each cost under the program’s control with the aim of reducing negotiated prices for contracts and obtaining other efficiencies in program execution to bring costs below those budgeted for the program. Any savings achieved can then be reallocated within the program or for other priorities.

The GAO found that 39 out of 43 current programs conducted a “should-cost” analysis. Of the 39 programs, 35 identified approximately $35 billion in realized and future savings. Those programs cited several activities as responsible for some or all its “should-cost” savings, including:

- Efficiencies realized through contract negotiations (15 programs)

- Design trades to balance affordability and capability (12 programs)

- Developmental or operational testing efficiencies (7 programs)

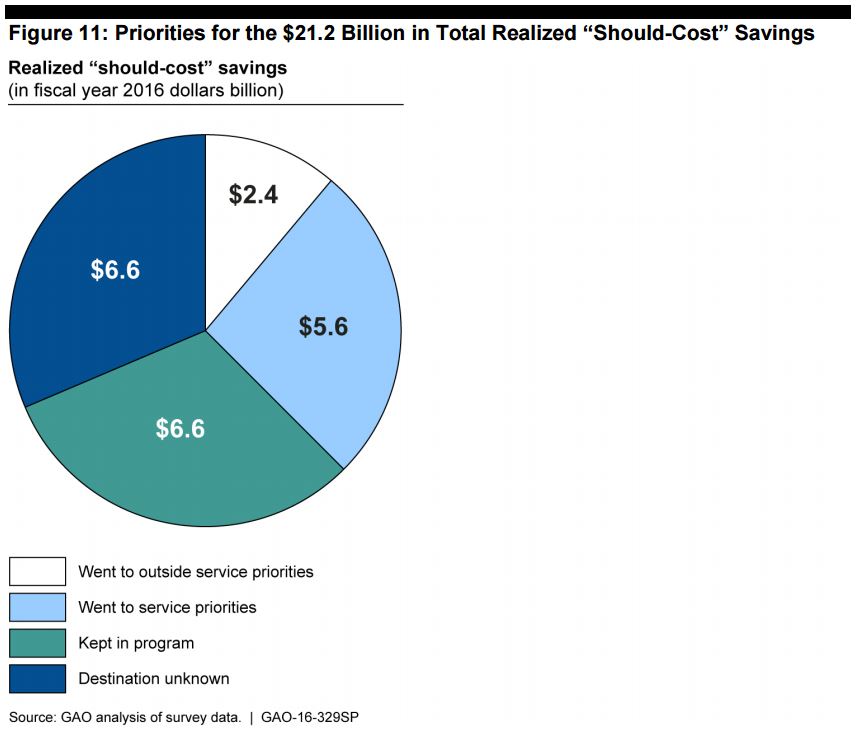

- Twenty-six of the 35 programs reported $21.2 billion in realized “should-cost” savings. Of this amount $3.4 billion in savings accrued from savings in development costs, $17.6 billion from procurement costs, and $0.2 billion from other sources. Programs also provided insight as to how their realized savings were allocated. Figure 11 shows the amount of savings reallocated to other purposes.

Of the $21.2 billion in realized “should-cost” savings, $6 billion was kept within the programs to fund other priorities. Programs reported that nearly $286 million of those savings were used to offset budget cuts required by sequestration. Another $5.6 billion of the realized “should-cost” savings went to priorities within the service to which the program belongs and $2.4 billion went to priorities outside of the service. While delivering value to the taxpayer in the acquisition process is one of DoD’s stated objectives, programs may not have strong incentives to realize or report “should-cost” savings if those programs perceive them as resulting in the funding of other DoD priorities. Programs we assessed were unable to account for the destination of roughly a third of the savings they reported.

Current programs that we surveyed expect to realize another $13.8 billion in future should cost savings. Of this amount, $8.5 billion in savings is expected to accrue for development and procurement “should-cost” savings and $5.3 billion is expected from other sources. Of the 12 future programs we assessed, 3 reported having conducted a “should-cost” analysis, and identified $9.6 billion in future development and procurement savings and an additional $7.9 billion in other savings.

Additional Should Cost Management Resources

- Should Cost Management Continuous Learning Module (DAU CLB 040), DAU, Nov 2016

- Product Support Should-Cost Opportunities, Marty Sherman and Bill Kobren, Defense AT&L Magazine, Nov 2017

- Should Cost: A Strategy for Managing Military Systems’ Money, Jennifer Miller, Defense AT&L Magazine, Mar 2016

- AFLCMC Standard Process for Should Cost Initiatives, Mar 2016

- Cost Capability Analysis – Introduction to a Technique, Frank Desling, Defense AT&L Magazine, Sep 2015

- Applications of Should Cost to Achieve Cost Reductions, Dr. Mark Husband, Defense ARJ, April 2014

- AFLCMC Perspectives on Will Cost/Should Cost Management, Janice Burke, Scott DeBanto, Mar 2014

- Should Cost Management in Defense Acquisition, Frank Kendall, USD/AT&L, Aug 2013

- Should Cost Management DAB Template, OSD/AT&L, Aug 2013

- Should Cost PEO Template for DAES Review, Jun 2013

- Should Cost PM Template for DAES Review, Jun 2013

- Should Cost Management Tactics, Dr. Mark Husband and John Mueller, Defense AT&L Magazine, Nov 2012

- The Air Force’s Experience with Should-Cost Reviews, RAND Corporation, 2012

- Should Cost Management: Why? How?, Dr. Ashton Carter, John Mueller, Defense AT&L Magazine, Sep 2011

- Should Cost and Affordability Memo, Dr. Ashton Carter, USD/AT&L, Aug 2011

- Target Affordability and Control Cost Growth Through Will Cost / Should Cost Management Brief, DAU, Aug 2011

- Navy memo: Implementation of Should Cost Management, Sean Stackley, ASN(RDA), Jul 2011

- Air Force memo: Implementation of Should Cost Management, David Van Buren, SAF/AQ, Jun 2011

- Implementation Memo of Will Cost and Should Cost Management, Dr. Ashton Carter, USD/AT&L, Apr 2011

- Air Force – Implementing Will-Cost and Should-Cost Management, Rebecca Davies, Ranae Woods, Air Force, Feb 2011

0 Comments