Considerations of Doing Business with the DoD

Intellectual Property

If you plan to do business with the Federal Government—specifically the Department of Defense—it is imperative that you understand their intentions for your intellectual property (IP) so that you can manage and transfer your IP in a way that is mutually beneficial. The most important thing to understand is that you and the Government are likely approaching IP ownership, as well as access and delivery, from opposite points of view. If you can’t reach a meeting of the minds, either you’ll give away the IP that is your company’s future bread and butter or the Government will be trapped in one of their biggest concerns, “vendor lock.”

Having opposite goals for your IP doesn’t mean that you can’t reach a compromise and that data rights and licenses can’t be negotiated. With understanding on both your parts, you can negotiate a win-win agreement that gives the Government everything they need while still being lucrative for you and your investors.

Why DoD Wants your IP | Government Terms for IP | Strategies & Tips for Protecting Your IP | References

Why the DoD Wants Your IP

The government wants to own your IP because their larger objective is to avoid vendor lock where they are at the mercy of a contractor and have almost no options but to accept increased prices, delayed schedules, and failed solutions.

To better understand the conflicting viewpoints, let’s look at recent history. Many of the senior Acquisition officials within Program Offices, specifically Program Managers and Contracting Officers, came of age in an era when the Federal Government was a significant source of research and development dollars. During that era, those contracts, especially those with small businesses that didn’t have a strong negotiating position, were often written to include unlimited data rights, which basically meant that anything developed to any degree under the contract belonged to the Government, not the creator or producer of the IP. The price of that data was sometimes listed as NSP or not separately priced, meaning that the price was included in the overall contract value. During this era, the primary exception for small businesses was the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program which granted “SBIR Data Rights” to the small business for—at that time—five years after the end of the last contract that used those rights. Large defense contractors tended to have top-notch negotiators and more IP lawyers to hammer out deals for limited rights or for technical data packages. They also had deeper pockets to develop new widgets on internal funding and could claim rights to in their proposals.

If you hang around with DoD acquisition professionals long enough, you’ll likely hear horror stories about getting stuck in a long-term series of sole source contracts for a product or service critical to national security and having to pay whatever the contractor demanded so industry partners wouldn’t “take their ball and go home.” This sense of vulnerability on the Government’s side to have to pay more than they felt they could justify and being stuck with that contractor’s high prices—throughout the life of not just that contract but multiple production lots—is a sore subject for some of the more experienced Government personnel you’ll meet. The experience with vendor lock has been painful enough that they don’t want to repeat it.

If they feel they’ve been burned by this situation in the past, they will be hyper aware of the need to maintain a competitive environment for as long as possible so that industry will be more compliant in terms, conditions, and lower prices.

This sense of vulnerability on the Government’s side… is a sore subject for some of the more experienced Government personnel you’ll meet. The experience with vendor lock has been painful enough that they don’t want to repeat it.

Being locked into a single vendor’s solution is, however, a real concern. If vendor lock prevents the Government from having another alternative to a particular weapons system, for example, then the solution to that warfighter need is in the hands of a contractor who:

-

- May not deliver on time, or

- May fail technically, or

- May not be willing to negotiate a price acceptable to the Government or within the Government’s budget for that program

A few decades ago, the Government reduced risk of this happening by carrying two contractors into or through production, but with reductions in budgets in recent years, this extended competition is often not feasible. The shift in negotiation power base to sole source contractors that retain their technical data rights can leave Program Offices feeling that they are at the mercy of that contractor since:

-

- Years of effort and funding would have to be re-accomplished to switch to a new contractor or

- The Government might pay an extraordinary amount to purchase the rights to recompete—and still end up with the incumbent, thanks to the kind of first-hand experience that doesn’t translate well into a technical data package.

Recent Real-World Events Affect IP

“In the cold war, 80% of the R&D in this nation was done by defense — now 80% of research and development is done by commercial innovation.” — Dr. Will Roper, Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics at Air Force Techstars 2020 Demo Day, “USAF’s New Strategy for Future Tech,” 30 May 2020.

Now that you understand why the Government might be nervous about not “owning the technical baseline” or controlling your IP, consider what happens when real world influences move faster than an acquisition culture that’s used to being in control. This section is not an indictment of how the Government did or does business but rather a deconstruction of fast-moving changes to which both Government and industry must react in order for both to win.

With an emergence of a Knowledge Economy and Fifth Industrial Revolution, knowledge—in this case IP—truly is power now. The usual “either-or” way of doing business—either unlimited rights where industry partners give away their future revenue for a small contract or limited rights that lead to vendor lock—no longer works, thanks to a shift in:

-

- Research funding,

- Game-changing technology being developed by non-traditional defense contractors

- Foreign threats

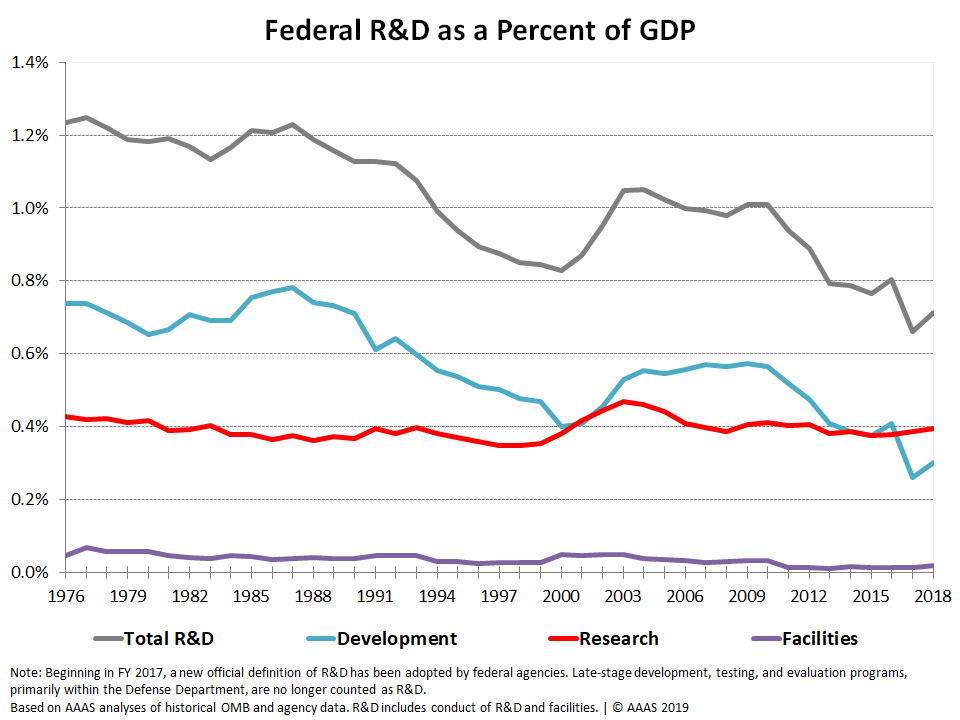

Whereas historically the Government provided the majority of research funds, that pattern is no longer true. According to National Science Foundation, National Patterns of R&D Resources survey data series, as recently as 1986, the Federal Research and Development (R&D) percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) was 1.21%, dropping to .66% in 2017.

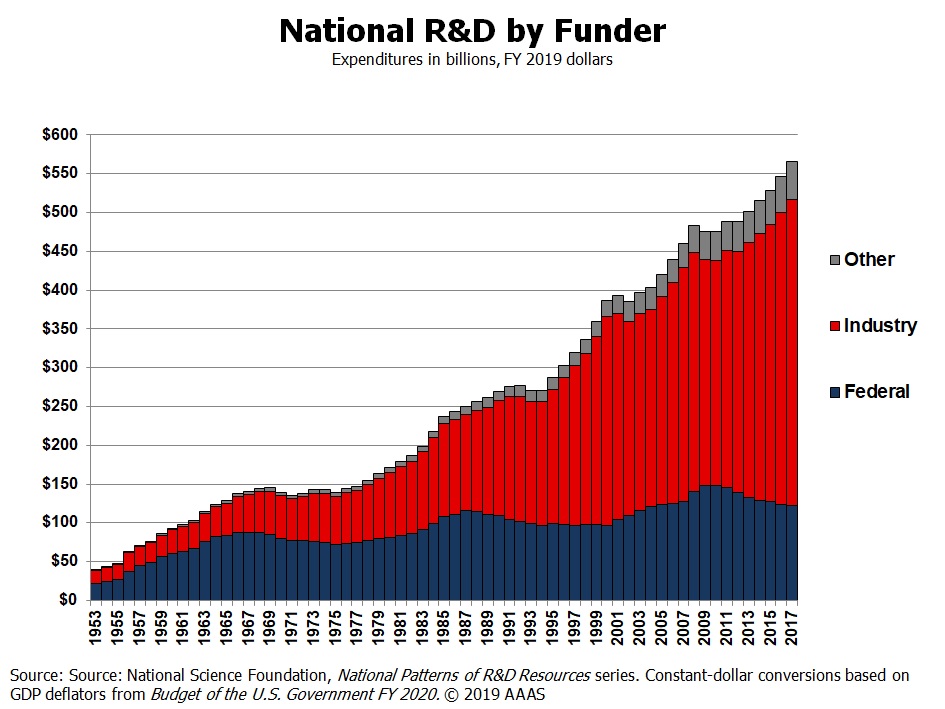

The Government’s contribution to research funding has wavered over the decades while industry’s contribution has consistently risen, significantly surpassing Government funding. For example, in 1965, in the first race for space, Government spending on R&D was $83.8B vs Industry’s $41.6B; in 2017 the Government’s contribution to R&D funding was $123B vs Industry’s $394.1B. These amounts do not include contributions from education, nor do they include the dangerous threat of foreign investments.

This shift in funding plays a significant role in what happens when the Government is no longer as prominent a source of R&D dollars as in the past. Not only does the Government have more difficulty enticing industry participation with a diminished role in providing R&D funds, but firms that have never worked with the Government, including small businesses and start-ups, may be able to secure funding much more quickly and more easily from venture capitalists than going through bureaucratic barriers to a Government contract. More disturbingly, those same small businesses may not be able to obtain funding fast enough from any US source and therefore accept investment funds from China, only to have their IP stolen within the year. Though there are several more foreign threats, China and Russia are openly discussed as foreign investors interested in game-changing technology that the US Government needs and must have to stay ahead of adversaries. Unlike the US Government contracts and agreements that identify limited data rights and US law that offers protection of IP (such as copyrights, trademarks, trade secrets, and patents), the IP of all industry in China and those doing business with those investors is at the convenience of the government of China. In regard to China, US Contractors have no protection for their IP, and China targets National Security technologies as part of their geopolitical strategy.

According to the downloadable white paper, “China, Silicon Valley, and National Security: Perspectives from the 2019 Offset Symposium,” China’s technology transfer methods are both legal and illegal, including corporate espionage and cybertheft. Chinese venture capitalists, according to the report, form a crucial part of their strategic goal of comprehensive national power.

If the next decade is to be a decisive contest between the United States and China, then the U.S. Government needs these game-changing technologies to stay ahead of peers in the Great Power Competition with China and Russia, “Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America, Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge“. Whereas in the past, industry needed the Government for R&D funding, now it is the Government that needs the new technologies that industry is exploring. This real danger of China or Russia overtaking the United States technologically is why the U.S. Government must now seriously look at lowering the barriers to industry, and this means that old ways of doing business are starting to change, including how the Government acquires or accesses IP.

Whereas in the past, industry needed the Government for R&D funding, now it is the Government that needs the new technologies that industry is exploring.

Government Terms for IP

The Government addresses technical data rights in three main ways, and they are named from the Government’s point of view. Be aware, too, that there are nuances between terms like Intellectual Property, licenses, and data rights that are often used interchangeably, and you might benefit from a consultation with an IP attorney. As a starter, casual explanations are provided below.

Unlimited data rights: The Government can do essentially whatever they want because the Government is “unlimited” in how they treat your technical data—including giving your data to your competitors or to the general public; your IP essentially belongs to the Government.

Limited data rights: The Government is “limited” in what they can do with your IP; it still belongs to the contractor but the Government can use the IP under that contract; they can’t give it to your competitors or the general public, legally, because they don’t have the right to give it away or share it without your permission.

Government Purpose Rights (GPR): The Government has rights to whatever was developed under mixed funding for (usually) five years. A common example is that the Government can use your IP, usually in the form of a technical data package, for the purpose of competing a follow-on contract.

The Government terms for IP*

1. Unlimited data rights

2. Limited data rights

3. Government Purpose Rights (GPR)

4. Specifically Negotiated License Rights

5. SBIR Data rights *Not all inclusive

The clause above also covers Specifically Negotiated License Rights, which is a license based on the mutually agreed upon modifications to unlimited rights, limited rights, and GPR. The benefit to you as a contractor is that in a FAR-based contract, whether you agree to unlimited rights, limited rights, or GPR, they are all negotiable and can be incorporated into the contract. However, many Contracting Officers are aware only of the three types of rights in technical data and don’t realize or know how to negotiate special licenses or arrangements. It’s possible but unlikely that their team’s legal counsel is an IP attorney.

Another type of data rights defined in DFARS is SBIR Data Rights, which allows the Government to have limited rights to the IP for a given period of time before becoming, essentially, unlimited rights that the Government can use as they wish, including giving it to your competitors or the general public. SBIR Data Rights are defined in DFARS clause 252.227-7018, Rights in Non-commercial Technical Data and Computer Software – Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Program, known informally as the SBIR Data Rights clause, which is being expanded as a result of the Section 813 Panel report. On 2 May 2019, the Small Business Administration updated this clause from the old five years from the end of the last contract to 20 years from the date of contract award. This protection applies to both SBIR and STTR (Small Business Technology Transfer) contracts. You can learn more about SBIR data rights protection through the SBIR Program’s tutorials.

Formal, comprehensive definitions of the first four data rights can be found in the DFARS clause, 252.227-7013, Rights in Technical Data – Noncommercial Items.

Prescriptions for other clauses, such as commercial use and software, can be found in DFARS Part 227.

Why you may have to teach the Government Contracting Officer

In the past, most Government contracts addressed data rights primarily in three ways: Unlimited data rights, Limited data rights, and GPR.

Many Contracting Officers are aware only of these three types of rights in technical data and don’t realize or know how to negotiate special licenses or arrangements. It’s possible but unlikely that their team’s legal counsel is an IP attorney.

As a result, they may retreat to the comfortable ground of unlimited rights without realizing your concerns for keeping your company alive. Industry and Government are two different worlds, and for as much as you may not understand about how the Government works, they are probably equally lost when it comes to what matters to you and why. It may be up to you to educate your counterpart that even a FAR-based contract with DFARS data clauses can still be negotiated in a way that’s good for both of you.

A popular viewpoint among industry partners is that FAR-based contracts are too inflexible when it comes to negotiating special licenses or unusual arrangements that might benefit both Government and Contractor throughout the life of their relationship. Contract language regarding IP is as flexible as the Contracting Officer feels equipped to be, plus whoever in their chain of command has approval authority over their final product. IP concerns can be creatively addressed in a FAR-based contract with a willing Government-Contractor team.

One of the more popular reasons for using Other Transaction Authority (10 USC 2371 and 2371b) is the perceived ability to be more creative with how IP is managed or transferred. Other transaction agreements allow the Agreements Officer (the Government Contracting Officer with special authority to write other transaction agreements) to write specific language regarding data rights, license agreements, etc. In some cases, the Agreements Officers are not comfortable with language other than the familiar DFARS clauses so they use DFARS language, either verbatim or paraphrased, and call it by another name. Renamed “copy-paste” language, however, is not the intent of other transaction agreements. Data rights and licensing language can be written creatively in both FAR-based contracts and other transaction agreements, though FAR-based contracts tend, at least for now, to be more traditional. Other transactions, on the other hand, are wide-open in how to craft IP-related language.

How Congress got the Government to think differently about IP

The thinking about how IP is handled in contracts and agreements shifted significantly when Congress mandated in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114-92), as amended in the FY2017 NDAA (Public Law 114-328), that a special advisory panel consisting of Government and industry experts be formed to review technical data rights, restrictions, and regulations and made recommendations for “tension points.” This advisory group, know as the Section 813 Panel, published the 2018 Report Government-Industry Advisory Panel on Technical Data Rights on 13 November 2018. The recommendations from the “813 Report” are broken down into eight key areas over a series of white papers that recommend changes to statutes, regulations, and policies.

If you don’t have time to read the full report—still worth reading at almost 200 pages—then read its Executive Summary (pages 4-7) or the National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA)’s 2-page Summary of the Section 813 Panel’s 2018 Report.

The following are the eight key areas addressed in the Section 813 Panel’s report:

Reference Source: Summary of the Section 813 Panel’s 2018 Report

Business Model Conflict

Government’s readiness to articulate long-term data requirements is lowest when industry’s readiness to accommodate is highest, and vice-versa.

Data Acquisition Planning and Requirements

The DFARS lacks guidance on government access to contractor data in the absence of a formal Contract Data Requirements List.

Source Selection and Post Source Selection IP Licensing

Source selections tend either not to include data access and rights as evaluation factors or to insist on stringent and inflexible data requirements. Government often makes special requests for technical data and software access that industry fears violate the federal regulations.

Balancing the Interests of the Parties

The extent of government rights to contractor IP depends on how regulations classify the source of funding for the underlying R&D. Controversy persists because in some cases contractors retain maximal IP rights despite receiving federal funding or reimbursement for their R&D.

Implementation

Implementation of data rights allocation requires assessing multiple content and source criteria that statutory and regulatory code currently inadequately define.

Compliance/Administration

Achieving compliance with data requirements forces contractors and government officials to solve complex technical, logistical, and personnel challenges.

Post Delivery Data Acquisition

Government’s deferred ordering of data imposes burdens on industry, while standard contract options for data rights restrict government’s ability to carry-out long-term sustainment plans for systems.

Modular Open Systems Approaches (MOSA)

Provisions in FY 2017 NDAA establish Government Purpose Rights (GPR) for technical data related to major system interfaces but this may place other privately developed contractor data at risk.

Eight Key Areas of the “813 Report”

1. Business model conflict

2. Data acquisition planning and requirements

3. Source selection and post source selection IP licensing

4. Balancing the interests of the parties

5. Implementation

6. Compliance/administration

7. Post delivery data acquisition

8. MOSA

Strategies and Tips for Protecting Your IP

Access vs delivery

Until recently, the Government has largely expected delivery of data, usually via a Contract Data Requirement List (CDRL), DD Form 1423, in accordance with DFARS 215.470. The data deliverables might have been a final report at the end of a study contract, a quarterly data accession list of all the contractor’s internal correspondence related to the project, PowerPoint charts of a program review, or a technical data package intended for future competition with other contractors.

However, delivery of data isn’t always necessary and, increasingly, access may be sufficient. In cases of information technology, for example, the Government may need only access to data through an application programming interface (API), to verify information in a database without needing to rights to a database they will never exploit, or access in the case of a cyber breach. The distinction between delivery and access has become more important with recent surges in certain technology areas whereas it would not have been as nebulous a decade ago.

delivery of data isn’t always necessary and, increasingly, access may be sufficient

Tips

#1: If access is more appropriate to the product or service you are providing to the Government, you may negotiate it in your FAR-based contract or in a statutory agreement such as an other transaction agreement under 10 USC 2371b. If the contract/agreement doesn’t include “boilerplate” for access, you can propose and negotiate it or you can agree that delivery is appropriate and price it accordingly. Remember, your Government counterpart may be unaware that access versus delivery is negotiable or may feel more comfortable with requiring delivery because that’s how they were taught.

#2: Before settling your negotiation, consider whether delivery will mean that you can never provide this product or service to another customer or if providing access-only will be enough to satisfy the Government’s needs.

#3: If you are giving away future revenue by agreeing to delivery and unlimited rights, ensure that your pricing reflects that choice. The Government may be willing to settle for access if the price is considerably cheaper.

Early Feedback and Proposed Language

You can help the Government Contracting team craft their acquisition strategy and encourage them to consider something more creative than a FAR-based contract with unlimited rights. If you’re late to the game and it’s negotiation time, you may still be able to ask for changes.

Tips

#1: Early in the market research and solicitation process, you can recommend to the Contracting/Agreements Officer the type of contract or agreement you prefer and the type of rights you’re willing to license. Ideally, the market research will take the form of some type of communications with industry, such as a Request for Information (RFI), which will ask you to provide information on your technologies, expertise, facilities, clearances, etc. If the RFI or its equivalent doesn’t ask you about IP and mentions only a contract (no other transaction), then this is the best time to give them the information they need to change their minds.

#2: If you receive or review a solicitation and don’t see IP and other transactions addressed, you can ask the Contracting Officer for clarification. The earlier you can influence the process, the better.

#3: Don’t be afraid to propose language, either for a FAR-based contract or an other transaction, but you don’t have to wait to write the proposal or negotiate it to influence the outcome.

Pricing IP

One of the more difficult parts of pricing your proposal and negotiating IP is figuring out how to assess value so that you don’t give away the farm upfront and yet not hanging on so tightly that the Government is locked into prices they won’t accept because they can’t justify them as “fair and reasonable.” The Government may want greater IP rights than customary in the commercial marketplace, and if you as an industry partner may not be sure-footed on how to price your IP rights, then your Government counterpart probably has less experience with IP valuation. Too often, the Government’s valuation of your IP is based on how much funding they have. For example, you may assess your IP’s value at $3M based on projected revenue or on how much internal funding you’ve spent to develop it, but the Government has only $300K in their budget.

Too often, the Government’s valuation of your IP is based on how much funding they have.

Tips

#1: If the Government asks you to provide a price for your technical data package so that they can compete it among your rivals, give them a firm number you can back up and walk them through it if necessary.

#2: If you will not under any circumstances agree to sell your IP, don’t be flippant and toss out numbers you can’t back up, like “$100B.” Your Government counterpart will need to document the price and will have hoops of their own to jump through.

#3: Be prepared to explain how you’ve priced your IP or what you’re willing to negotiate for the funding available. Neither the Government nor industry seem to have a good handle yet on how to valuate IP and therefore negotiate rights or licenses; although the Government is beginning to look at accepted best practices/norms/standards, this new skillset is a work in progress. This change won’t happen overnight, so it’s better to be prepared.

Your IP Strategy

The DoD must include an IP strategy in the acquisition strategy from the very beginning of the acquisition process, when the first study contracts and prototype agreements are written, rather than waiting to consider IP before awarding a high-dollar, sole source production contract.

Tips

#1: Know where you want your company to go so that you don’t waste resources on the wrong Government contacts or the wrong projects that won’t further your company’s goals.

#2: Bake in your IP plan from the very beginning. This means having your own IP strategy across all phases of acquisition or, if you are looking for only a short-term partnership with the Government, an IP strategy that covers where you plan to go with your business after the contract ends so that you don’t give away your IP for short-term gain. Think long-term about where you see your IP, even if you don’t plan to have a long-term relationship with the Government.

#3: Know what’s negotiable to you and what’s not. Know before you spend resources writing a proposal for a Broad Agency Announcement (BAA), what rights you are willing to give away? What rights do they state in the solicitation will be required or do they tell you that data rights and licenses are negotiable?

#4: Ask questions during any open communication period with the Government before you commit resources rather than submit a proposal for a contract with terms you may not be willing to accept.

#5: If you miss the open communication period, send a written request for clarification to the Contracting Officer because at some point, communications will probably be reduced to only through the Contracting Officer to ensure fair communication with all potential Contractors.

IP Lawyers

Tips

#1: Consider consulting with an IP lawyer. Although it isn’t necessary to have an IP lawyer on staff, you may wish to engage with a lawyer who specializes in IP rather than your staff lawyer or regular attorney. This can be expensive, particularly if you have to bring in your own IP lawyer to negotiate IP.

#2: Be prepared to negotiate with the Government’s IP lawyer. Because very few Contracting Officers have extensive experience in IP negotiations, they may bring their IP lawyer to the negotiation table, in the rare case they have an IP lawyer, so educate yourself beforehand on how to manage your IP, valuation, etc. Even to submit a proposal, you may need to consult a lawyer who understands IP, so legal advice may be an unanticipated expense.

Assertion of Rights

Tips

#1: Be sure to identify IP that you already have rights to in your proposal if you plan to use it in your contract performance, usually in Section K of the solicitation or somewhere in your proposal.

#2: Before you sign a contract or agreement, make sure that the pre-contract IP to which you asserted rights is included in the contract or agreement, often in an attachment.

#3: Don’t asserts rights to software you’ve purchased commercially, such as Microsoft Excel. You might create a spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel that you assert rights to because it includes a formula you plan to use during the course of the contract, but you wouldn’t claim Microsoft Excel or any of Microsoft Office products that you use in your daily operations because you didn’t develop Microsoft Office.

References

Reports and White Papers

- “Department of Defense Access to Intellectual Property for Weapon Systems Sustainment,” aka “Section 875 Report,” INSTITUTE FOR DEFENSE ANALYSES

- 2018 Report Government-Industry Advisory Panel on Technical Data Rights, aka “Section 813 Report,” 13 November 2018

- National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA)’s 2-page Summary of the Section 813 Panel’s 2018 Report

- NCSC/ODNI: 2018 Foreign Economic Espionage in Cyberspace

- “China, Silicon Valley, and National Security: Perspectives from the 2019 Offset Symposium”

Data

National Strategy and NDAAs

- 2018 National Defense Strategy Summary

- National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2017 (Public Law 114-328)

- National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114-92)

Webinars

- Intellectual Property and Data Rights Overview, DAU, Mark Dvorscak, 8 June 2020

- Army’s New Intellectual Property (IP) Policy, DAU, Vicki Allums, 20 September 2019

- Navigating Data Rights, Intellectual Property, and Contracting Issues in Cloud Computing Contracts – Some Common Sense Best Practices, DAU, Bill Bahnmaier, 25 July 2019

- Maintaining DoD’s Technological Advantage: The Role of Intellectual Property (IP): IP Strategies, Segregation, & Modulation, DAU, Vicki Allums, 15 April 2019

- Intellectual Property Strategy, DAU, Ivan Teper, 26 June 2018

Other

- “USAF’s New Strategy for Future Tech,” Medium, 30 May 2020

- Federal R&D Budget Dashboard