Considerations of Doing Business with the DoD

Supply Chain

Managing supply chain risks is an area of Federal acquisition that has gained greater attention the last few years due to an improved understanding of the potential risks to Government systems. Conducting business with the DoD or the U.S. Government calls for an understanding the source of this focus, the latest policy developments, and potential information that you may be asked for to verify the security of their supply chain or to assist in the program protection planning of a Government system. If operating in the technology space, especially as it relates to a defense weapons system or important Government system, you must be very cautious of foreign capital and the potential or perceived influence of that capital.

Defense Science Board Study | Executive Order Report | Congressional Action | CFIUS | IT Executive Order | Cybersecurity |

Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification | Supply Chain Expectations

Defense Science Board Study

A major development in Government officials gaining an understanding of potential supply chain risks posed by foreign adversarial governments was a study conducted by the Defense Science Board in 2017 titled the “Task Force on Cyber Supply Chain”. In it, they found that the United States’ weapons systems are at risk from the malicious insertion of defects or malware into microelectronics and embedded software, and from the exploitation of latent vulnerabilities in these systems.

They recommended that the DoD take various actions, to include:

- Expanding vulnerability assessments

- Improving detection and reporting

- Enhancing program protection planning

- Improving timeliness of supplier vetting

- Considering cybersecurity impact of COTS products and components

- Establishing sustainment program protection plans for fielded systems

- Collecting and acting on parts vulnerabilities

Executive Order Report

Another threat to the DoD supply chain was illuminated in a September 2018 report to the President titled“Assessing and Strengthening the Manufacturing and Defense Industrial Base and Supply Chain Resiliency of the United States.” In it, the authors highlighted that the Chinese Communist Party’s “Made in China 2025” initiative was targeting key innovative technology sectors in the United States, such as artificial intelligence; quantum computing; robotics; autonomous and new energy vehicles; high-performance medical devices; high-tech ship components; and other emerging industries that are all critical to national defense.

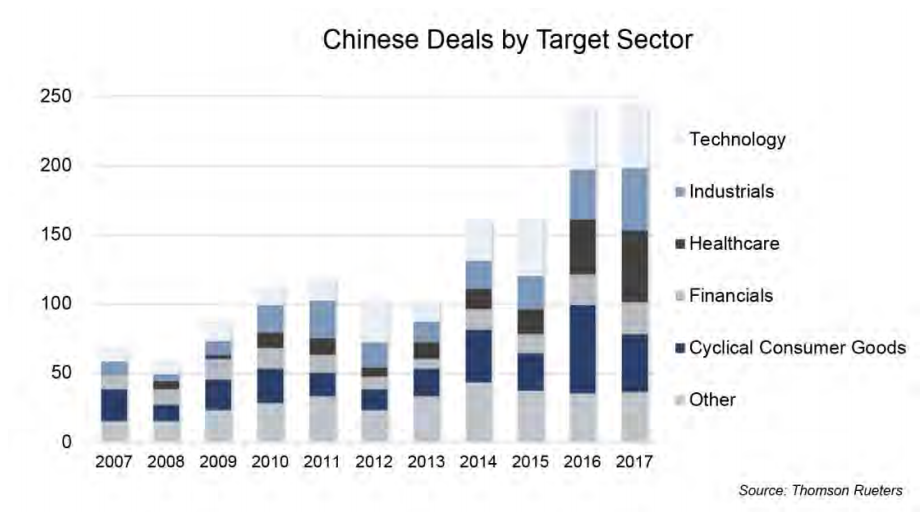

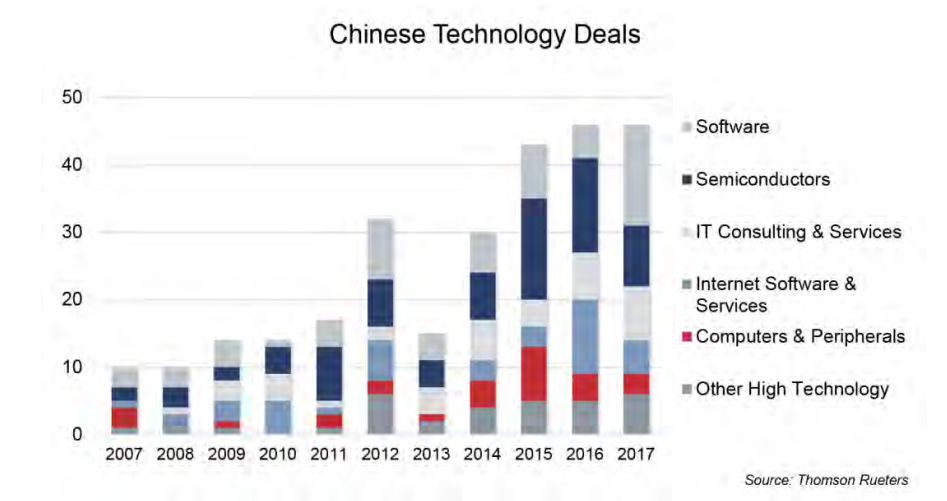

The report noted that China relies on both legal and illicit means, including foreign direct and venture investments, open source collection, human collectors, espionage, cyber operations, and the evasion of U.S. export control restrictions to acquire intellectual property and critical technologies. In terms of foreign direct investment, the Chinese government allocated $46 billion in 2016 for U.S. technology sectors. This represented triple the previous year and a tenfold increase from 2011. The below figures illustrate how China is targeting key technology sectors with its state-supported foreign direct investment.

Congressional Action

In response to these threats and the increasing potential that U.S. firms may trade managerial control in return for Chinese Communist Party financial investments, the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) of 2018 was passed by Congress and signed into law by the President on August 13, 2018. This act strengthened and modernized the capabilities of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) to address national security concerns more effectively, including broadening the authorities of the President and CFIUS to review and to take action to address any national security concerns arising from certain non-controlling investments and real estate transactions involving foreign persons.

Under FIRRMA, a U.S. company that “produces, designs, tests, manufactures, fabricates or develops one or more critical technologies” may undergo heightened scrutiny by CFIUS. There are 14 broad categories of technology which are expected to be focused on:

- Biotechnology

- Artificial Intelligence (AI)

- Position, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) Technology

- Microprocessor Technology

- Advanced Computing Technology

- Data Analytics Technology

- Quantum Information and Sensing Technology

- Logistics Technology

- Additive Manufacturing (e.g., 3-D printing)

- Robotics

- Brain-Computer Interfaces

- Hypersonics

- Advanced Materials

- Advanced Surveillance Technologies

To trigger the mandatory CFIUS filing requirement under current regulations, the U.S. business which receives foreign investment must also operate in one of 27 high-risk industries identified by their North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code:

|

Aircraft Manufacturing |

Aircraft Engine and Engine Parts Manufacturing |

Alumina Refining and Primary Aluminum Production |

Ball and Roller Bearing Manufacturing |

|

Computer Storage Device Manufacturing |

Electronic Computer Manufacturing |

Guided Missile and Space Vehicle Manufacturing |

Guided Missile and Space Vehicle Propulsion Unit and Propulsion Unit Parts Manufacturing |

|

Military Armored Vehicle, Tank, and Tank Component Manufacturing |

Nuclear Electric Power Generation |

Optical Instrument and Lens Manufacturing |

Other Basic Inorganic Chemical Manufacturing |

|

Other Guided Missile and Space Vehicle Parts and Auxiliary Equipment Manufacturing |

Petrochemical Manufacturing |

Powder Metallurgy Part Manufacturing |

Power, Distribution, and Specialty Transformer Manufacturing |

|

Primary Battery Manufacturing |

Radio and Television Broadcasting and Wireless Communications Equipment Manufacturing |

Research and Development in Nanotechnology |

Research and Development in Biotechnology (except Nanobiotechnology) |

|

Secondary Smelting and Alloying of Aluminum |

Search, Detection, Navigation, Guidance, Aeronautical, and Nautical System and Instrument Manufacturing |

Semiconductor and Related Device Manufacturing |

Semiconductor Machinery Manufacturing |

|

Storage Battery Manufacturing |

Telephone Apparatus Manufacturing |

Turbine and Turbine Generator Set Units Manufacturing |

|

Check out this CFIUS tool that helps you assess potential CFIUS filing obligations or compliance with law (Note: this does not constitute endorsement of the firm).

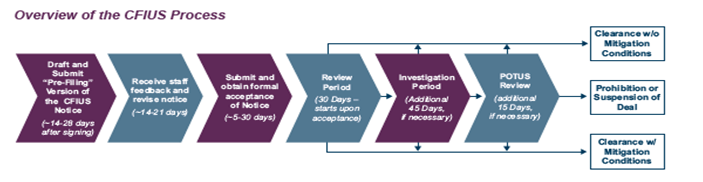

The CFIUS Process

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is a Federal interagency committee chaired by the Secretary of the Treasury. Additional members of CFIUS include the Secretaries of Homeland Security, Commerce, Defense, State, Energy, and Labor, the Attorney General, the Director of National Intelligence, the U.S. Trade Representative, and the Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy.

Image Credit: Latham & Watkins, LLP

CFIUS was created in 1988 by the Exon-Florio Amendment to the Defense Production Act of 1950. CFIUS’ authorizing statute was amended by the Foreign Investment and National Security Act (FINSA) of 2007.

This statutory framework authorizes the President of the United States (through CFIUS) to review “any merger, acquisition, or takeover … by or with any foreign person which could result in foreign control of any person engaged in interstate commerce in the United States.”

CFIUS’ role is to evaluate whether and to what extent such transactions could impact U.S. national security. If a transaction could pose a risk to U.S. national security, the President may suspend or prohibit the transaction, or impose conditions on it.

A CFIUS determination that a transaction could threaten or impair national security does not necessarily mean that the transaction will not be allowed to move forward. Indeed, very few transactions have ever been rejected outright through the CFIUS process (although from time to time parties have withdrawn their transactions from review and terminated those transactions when the likelihood of an unsuccessful outcome became clear). In many cases, CFIUS can clear a transaction subject to conditions designed to mitigate the perceived risks to U.S. national security the transaction otherwise would pose. (Source: Latham & Watkins, LLP Overview of the CFIUS Process)

Image Credit: Latham & Watkins, LLP

Information Technology Executive Order 13873

In Executive Order 13873 of May 15, 2019, titled “Securing the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain”, the President identified that “foreign adversaries are increasingly creating and exploiting vulnerabilities in information and communications technology and services, which store and communicate vast amounts of sensitive information, facilitate the digital economy, and support critical infrastructure and vital emergency services, in order to commit malicious cyber-enabled actions, including economic and industrial espionage against the United States and its people.”

To counteract this threat, the President prohibited: any acquisition, importation, transfer, installation, dealing in, or use of any information and communications technology or service where the transaction has been determined to involve:

- Information and communications technology or services designed, developed, manufactured, or supplied, by persons owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of a foreign adversary.

- Poses an undue risk of sabotage to or subversion of the design, integrity, manufacturing, production, distribution, installation, operation, or maintenance of information and communications technology or services in the United States.

- Poses an undue risk of catastrophic effects on the security or resiliency of United States critical infrastructure or the digital economy of the United States.

- Otherwise poses an unacceptable risk to the national security of the United States or the security and safety of United States persons.

Cybersecurity

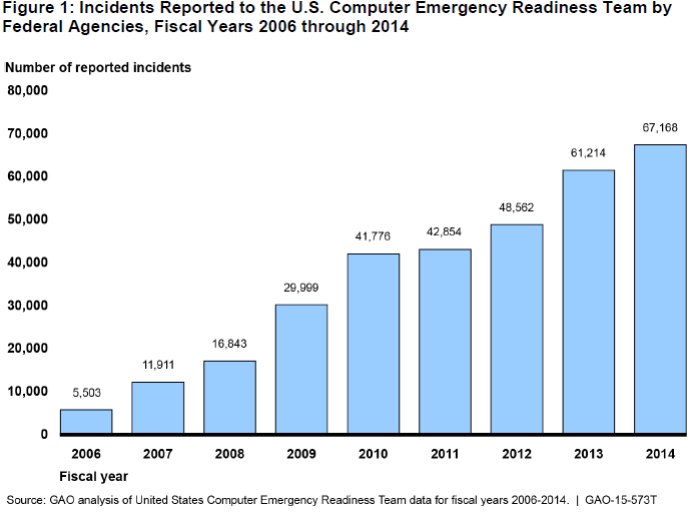

In February 2015, the Director of National Intelligence testified that cyber threats to U.S. national and economic security are increasing in frequency, scale, sophistication, and severity of impact. The Council of Economic Advisers, an agency within the Executive Office of the President, estimates that malicious cyber activity cost the U.S. economy between $57 billion and $109 billion in 2016, with some estimates putting that number much higher. Cybersecurity is a critical aspect of weapons systems design, and over the last few years its criticality has gained much more attention.

However, it has also been realized that it is not enough to just secure the weapons system. U.S. adversaries have been able to exploit vulnerabilities across the larger DoD supply chain by stealing intellectual property and potentially compromising important systems. These vulnerabilities can be found in contractor facilities, including design, development, and production environments, networks, supply chains, and personnel, which can act as cyber pathways for adversarial actors to access Government program organizations or fielded systems to steal, alter, or destroy system functionality, information, or technology.

A 2015 Government Accounting Office (GAO) report highlighted that not all cyber intrusions result from unintentional threats “caused by, among other things, defective computer or network equipment, and careless or poorly trained employees” and that cyber incidents are on the rise, which demands a Government response.

Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC)

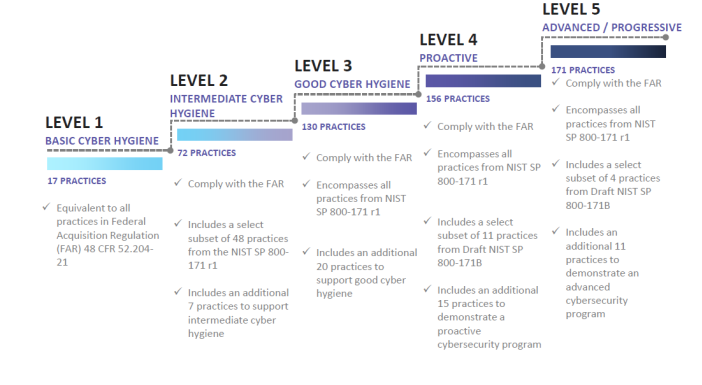

To ensure that the larger Defense Industrial Base (DIB) supply chain has the appropriate level of cybersecurity to stem the loss of Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI), the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (USD A&S) initiated the CMMC initiative. The intent is to incorporate CMMC into the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), building on to clauses already in existence (such as DFARS 252.204-7012) and to eventually use it as a requirement for contract award. To date, OMB has not instituted the DFARS revision, so there are no mandatory CMMC requirements currently in place. If implemented as envisioned, CMMC will encompass multiple maturity levels that range from “Basic Cybersecurity Hygiene” to “Advanced/Progressive.”

Note that CMMC certification does not denote achievement of supply chain security nor represent the entirety of cybersecurity measures that your company might want/need to adopt.

Image Credit: CMMC Model v1.0 Public Briefing, 31 January 2020

Points of Clarification

- If your company solely produces Commercial-Off-the-Shelf (COTS) products, a CMMC certification will not be required.

- CMMC applies to only your unclassified networks that handle, process, and/or store Federal Contract Information (FCI) or CUI.

- If your company does not possess CUI but possesses FCI, it must be certified at a minimum of CMMC Level 1.

- The level of certification required will be driven by individual programs as captured in the Requests for Information or Proposals submitted by the Government.

- The certification will be conducted by Third Party Assessment Organizations (C3PAOs) under the auspices of the CMMC. Accreditation Body (AB) cmmcab.org. The CMMC AB is establishing a CMMC Marketplace where DIB companies will be able to select one of the approved C3PAOs and schedule a CMMC assessment for a specific level.

- A CMMC certificate will be valid for three years.

Expected Costs

To be determined, but expected CMMC assessment costs will depend upon several factors to include the CMMC level, the complexity of your company’s network, and other market forces.

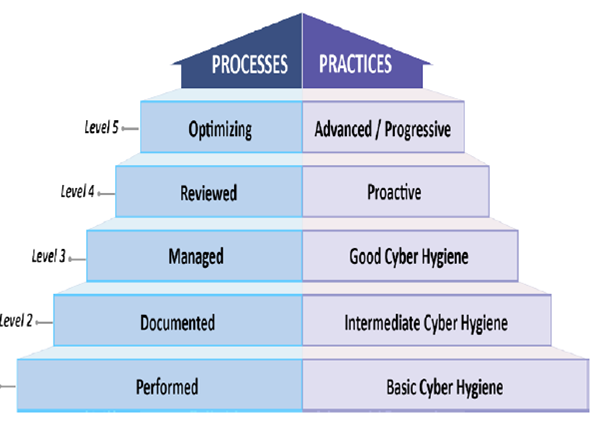

CMMC Specific Processes and Practices By Level

Your company will be expected to demonstrate both the institutionalization of the processes and the implementation of the practices to certify at that level. Source: CMMC Appendices

Image Credit: CMMC Model v1.0 Public Briefing, 31 January 2020

Supply Chain Expectations

To this end, when competing for and negotiating a DoD contract or agreement, you will increasingly notice that there is a heightened focus from Government program officials on ensuring that the product you are providing has a secure supply chain both for hardware and software. You may notice this in a variety of ways:

- You will likely be requested to obtain a Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification in order to bid on certain Federal contracts.

- You may be requested to provide details about any ownership or control your company may have from countries that are unfriendly or adversarial to the United States.

- You may be requested to identify contractual obligations, technical or research agreements, or other information exchange efforts that you have with countries that are unfriendly or adversarial to the United States.

- You may be requested to identify component suppliers or original equipment manufacturer vendors with headquarters, manufacturing, distribution, or RDT&E facilities within countries that are unfriendly or adversarial to the United States.

- You may be requested to identify the corporate and technical processes you use to mitigate the risk of malicious insertion or compromise in your products’ design, manufacturing, and distribution supply chain.

- You may be requested to explain the supply chain process you employ to mitigate counterfeit parts being included in systems delivered to the U.S. Government.

- You may be requested to identify the system design principles you follow to ensure that hardware or software is not configured in such a way that an adversary might initiate network connections and/or data transmissions to an external network or initiate a catastrophic failure.

- You may be asked to provide illumination of your supply chain through the provision of a hardware/software Bill of Materials.

- You may be requested to explain any significant malicious network intrusions or significant data breaches your company experienced that led to loss of client data or intellectual property and what actions are being taken to avoid any reoccurrences.

- You may be requested to explain how your company incorporates resilient design methods that include rapid isolation of subsystems based on detection of aberrant behavior.

- You may be requested to explain how your system design includes active search and continuous automated monitoring to detect system failure.

- You may be requested to explain how your company apples technical methods to identify discrepancies in software, including code, and firmware to screen for malicious code and hardware abnormalities.

- You may be asked to assist in the development and update of Program Protection Plans (PPPs) for defense acquisition programs. A PPP is a single source document used to coordinate and integrate all protection efforts for an major defense acquisition program and is used to manage risks to advanced technology and mission-critical system functionality from foreign collection, design vulnerability, or supply chain exploit/insertion, and battlefield loss throughout the acquisition lifecycle.