Disrupting Acquisition Blog

Principles of War, Axioms of Acquisition

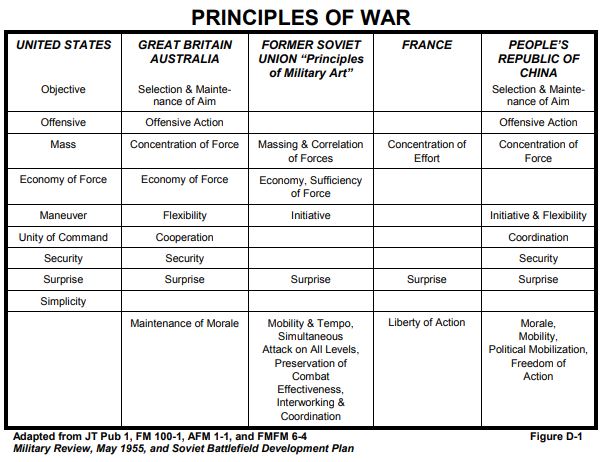

Honed by hundreds of years of battlefield experiences, many militaries have developed “Principles of War” to represent leading truths in the conduct of warfare. Not surprisingly, there is overlap between various statements of such principles. Offensive, Surprise, Economy of Force, Objective, Security and Mass are a few of the widely-shared principles across many militaries.

Military officers are taught that to ignore the Principles of War is to court disaster in the field. While following the Principles of War brings no guarantee of success, it’s certain that violating the Principles of War entails great risk and has a poor wartime track record. For fighting a current conflict, it’s wise to hew to the Principles of War as a nation deploys its’ fielded military capability. But what about getting ready to fight a future war?

Sadly, there’s always going to be a next war. Getting ready to prevail in a future conflict is not about applying the Principles of War using existing forces. It’s about the decisions, investments and actions taken in the years prior to a conflict — which result (or not) in prepared military members wielding war-winning capabilities, fielded in sufficient quantity, in time to be useful in the next conflict. This pre-conflict process contains at least three key elements. The first concerns the human element — the accession, training, and readiness of the men and women comprising the fighting force. The second concerns the materiel element — the development, fielding, and sparing of war-winning military hardware and software. The third concerns the doctrinal element – the methods and techniques for how the first two elements are best used on the battlefield. The second element is often referred to as Acquisition, especially when taken in the larger strategic sense of the word. For Strategic Acquisition in particular, can the Principles of War help us prepare for future conflicts? The answer is yes — although with a few twists – since many of the Principles of War still make sense when preparing during a time of peace. Here’s an attempt to re-purpose some Principles of War into proposed “Axioms of Acquisition.”

[For those with serious geek street cred, the Axioms of Acquisition are not the same as the Laws of Acquisition followed by the Ferengi in Star Trek. Sorry.]

Proposed Axiom #1: Simplicity

This axiom is drawn directly from the US Principle of War of the same name. In the warfighting context, simplicity refers to straightforward goals, use of mission orders, battle plans that are not needlessly complex, etc. Such plans and goals are easier to understand and are more likely to be implemented successfully. As with combat operations, acquisition programs benefit from having “clear, uncomplicated plans.”

Applying the Axiom of Simplicity in an acquisition context involves actively reducing unnecessary complexity across the entire spectrum of decision-making, from requirements and system architectures, to procedures and documentation. Rather than treating complexity as a desirable indicator of sophistication, this axiom affirms an observation from the 2006 Defense Acquisition Performance Assessment report which stated “complex acquisition processes do not promote program success – they increase costs, add to the schedule, and obfuscate accountability.”

The Simplicity Cycle provides a visual framework for identifying and removing unnecessary complexity, and can help teams have meaningful conversations about complexity and simplicity in their programs.

Proposed Axiom #2: Liberty of Action

France (Liberty of Action), the PRC (Freedom of Action), and UK/Australia (Flexibility) all have a principle that values the ability and the freedom to take action in the moment based on circumstances. This is vital since war takes place in a wicked environment that is dynamic, volatile and complex – and good commanders are constantly learning, revising their views, and hopefully then having the liberty of action to respond. The same holds true for acquisition, which also occurs in a wicked environment even if the time pressures are not quite the same. An added complexity factor is that acquisition is essentially a political activity given the need for transparency and fairness in contract awards. Successful acquisition portfolios navigate this environment by reacting to changing conditions and new information – which is enabled by having enough liberty to take action in a relevant timeframe – sometimes called Permission-less Innovation. This axiom is supported by the next axiom.

Proposed Axiom #3: Unity of Decision-making

Closely related to the previous topic is the US principle called Unity of Command. While never absolute, US warfighting doctrine puts great stock in a single commander having the responsibility and authority to make command decisions. It’s hard to take action in the moment when a commander has to ask for approval. It’s hard to have Liberty of Action if you don’t have Unity of Decision-making. In an acquisition context, this means having a (portfolio) leader with enough authorities in key areas – requirements, technical, contracting, resourcing, personnel, etc – in order to take action in a relevant timeframe. While recent moves to take OSD out of program oversight are a huge step in the right direction, there are still far too few acquisition leaders with true unity of decision-making.

Proposed Axiom #4: Stability of Resourcing

Both France and the PRC have a principle called Concentration of Effort, which aims to put maximum effort and forces on the most important objectives – and not continually changing those important objectives. While perhaps a bit of a stretch, a corollary acquisition axiom promotes the importance of having mission/portfolio priorities that lead to stable acquisition resourcing. While the reality of the world is that priorities do change and shift, constant funding churn with the resulting uncertainties and required re-work are the bane of any program manager or portfolio executive. In a sense, it doesn’t matter the absolute amount of the resources. More important is that stability of resourcing allows commitment to a sustained effort over time. A related attribute is that stable resources enable building in resource buffers to deal with the always-present difficulties that occur in any sufficiently complex portfolio. This axiom is where the current Executive and Congressional budget processes most fall short.

Proposed Axiom #5: Frequent Fielding in Quantity

An apocryphal quote from the Civil War said it was imperative to “Git thar fustest with the mostest.” From a principle of war perspective, grouping forces (US principle of Mass) at a time and place that shocked the enemy (US principle of Surprise) could lead to decisive battlefield advantage. This applies just as much to strategic acquisition. Fielding new and advanced capabilities can certainly surprise potential adversaries. Doing so frequently challenges their reaction OODA loop – complicating their own modernization and technology efforts. It also has the knock-on benefit of allowing our warfighters to more rapidly evolve tactics and strategies – and refine requirements for the next round of fielding. But fielding novel capabilities in itself is not enough – there has to be enough quantity to yield a warfighting advantage. As an example, the Germans in WW II unquestionably had better technology than the Allies in many areas – the first jet fighter (ME-262), the first cruise missile (the V-1), and the first intermediate range ballistic missile (V-2). Yet none of these capabilities were fielded in enough quantity to yield a large warfighting advantage, especially in the face of the huge types and quantities of “good enough” systems fielded by the Allies.

Let’s be honest — acquisition is boring. It lacks the grandeur of ships steaming, aircraft strafing, tanks pulverizing far away targets, and steely-eyed military members executing their craft. The level of urgency is different — split-second decisions are not required. Nonetheless, lives are at stake in Strategic Acquisition — not immediately, but definitely in the future. Just because the good or bad results of Strategic Acquisition might happen years from now does not make the consequences any less real or the need for success any less important. As renowned historian I.B. Holley said after WWII, “[T]he procurement process itself is a weapon of war no less significant than the guns, the airplanes, and the rockets turned out by the arsenals of democracy.”

I’ve proposed five Axioms of Acquisition that point the way to higher chances of Strategic Acquisition success. Just as battlefield commanders ignore the Principles of War at their peril, we ignore the Axioms of Acquisition at our long-term peril.

If you’ve got comments and thoughts on evolving these proposed Axioms of Acquisition, please share them below.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are those of the authors only and do not represent the positions of the MITRE Corporation or its sponsors.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

0 Comments