Disrupting Acquisition Blog

The Program Side of the Valley of Death

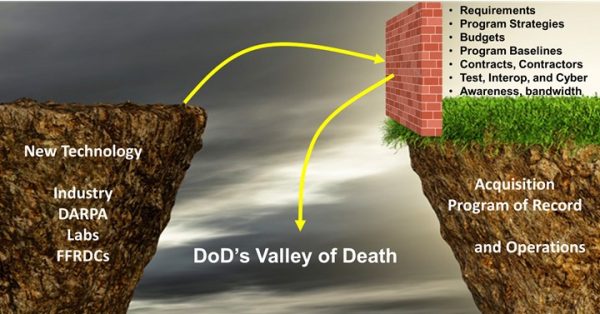

The DoD’s Valley of Death continues to be a major issue as it struggles to rapidly exploit leading defense and commercial technologies for the next generation of military capabilities. The future of warfare will be won by those nations that can effectively harness artificial intelligence, autonomy, cyber, quantum, and related leading technologies… and adapt its way of fighting. The Valley of Death discussions point to the issues with the long timelines for budgeting and the bureaucracy to capture and scale promising science and technology prototypes and projects. Yet the one area that is rarely discussed is the program side of the Valley of Death.

Imagine if a technology manager from DARPA, a DOD Lab, or industry knocked on the door of an acquisition program manager and said: “Boy do I have something to show you! This new technology will double your system performance at half the cost!” After a demonstration or discussion of the details, the program manager may say: “Wow, this is amazing! This is game changing for DoD! But sadly, I can’t use this. Thanks for coming by.” The shocked technology manager will ask why and the program manager will say:

- We just spent two years getting the program’s requirements document approved through JCIDS. This new technology may fit within the scope of the operational needs, but the requirements document would need to be updated to reflect the details of this technology insertion and re-staffed up to Joint Staff.

- We just spent nearly two years developing dozens of program strategy documents, coordinating them through dozens of oversight organizations, along with dozens of reviews and meetings. We would need to update the acquisition strategy, systems engineering plan, test and evaluation management plan, and dozens more to integrate the new technology and re-staff for approval.

- After a lengthy, brutal budget battle over the last three years, we got funding for the program. While the cost of the technology may be cheaper than what we currently are developing, there is integration and rework costs. We would have to spend months to estimate the costs to acquire, scale, and integrate the technology and see if this fits within the scope of my appropriated budget from a description and funding amount.

- Following our Milestone B, my program’s cost, schedule, and performance were baselined in an Acquisition Program Baseline (APB). That is my contract with my decision authority on how the program will be constrained and I’m held accountable. These changes would drive a breach to my APB, which comes with additional oversight scrutiny by OSD, Congress, and GAO adding risk to the program.

- After a year long source selection and negotiations, we awarded a major contract with a defense prime contractor. This new technology is far better than what they are developing, but to pivot to this new solution would hurt their business model. They will fight this contractually, legally, and lobby Congress to defend their existing work. The company that did not win the source selection was very close to protesting and I worry that if we radically change the scope of the contract, they will call foul which could put the program on hold. Regretfully we do not own the technical baseline nor implement a modular open systems approach with this program, so tech insertion is very difficult.

- The stakeholder and oversight organizations responsible for testing, interoperability, and cybersecurity would need to update strategies, assessments, and certifications to address this new technology.

- My overworked program staff and the contracting office don’t have the time to do another round of market research to see if there are other viable alternatives to this new technology solution or other companies with a similar capability.

I love this new technology and see the huge potential this offers the DoD! Regrettably, I would need to spend 6-12 months to change all of the above things and coordinate with dozens of different oversight organizations to integrate your new technology. That poses a major risk to the overall program and delays fielding capabilities to the warfighters who are operating with 30-year-old legacy systems. Maybe my successor can integrate your technology in a follow-on system upgrade in a few years.

Now if you’ll please leave, I’m late for my monthly program EVM meeting.

Until DoD works through each of these issues to break down the programs barriers, throwing billions more at SBIR, labs, and startups won’t matter much. DoD needs to pivot from a program-centric system to one where portfolios regularly deliver an integrated suite of capabilities. The JCIDS requirements process is still in dire need of an overhaul for the 21st Century. With the current dynamic environment of emerging technologies, threats, and operations, DoD needs to move away from strict program baselines that falsely assume a stable environment for a decade of development and production. For the successful science and technology capabilities and commercial solutions, Congress and DoD need to authorize many more new programs to scale them. DoD can no longer afford to have these too-big-to-fail major systems with winner take all competitions that shape a defense sector for the next decade. It needs portfolios of solutions with continuous competition and iterate upgrades every year or two.

These are the steps DoD must take to ensure a robust National Security Innovation Base fuels innovative defense solutions for decades ahead.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are those of the authors only and do not represent the positions of the MITRE Corporation or its sponsors.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter