Disrupting Acquisition Blog

SASC Hearing on the Defense Industrial Base

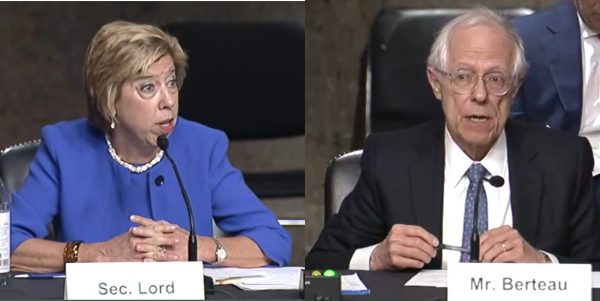

The SASC recently held a hearing on the Health of the Defense Industrial Base. The witnesses were Ms. Ellen Lord, former USD(A&S) and President/CEO of Textron Systems and Mr. David Berteau, President/CEO of the PSC and former ASD/LMR. I wanted to highlight some of their key remarks for increased visibility.

Chairman Jack Reed

- I am concerned by the impact of the long-term trend in consolidation of private companies participating in defense research, development, and acquisition, especially since the Cold War drawdown in the 1990s.

- Competition within the defense industry is vital to fostering innovation, delivering products and services in a timely and efficient manner, and keeping costs in check.

- However, in the last three decades the defense sector has consolidated substantially, transitioning from 51 aerospace and defense prime contractors down to just 5.

- That has unintended consequences on costs, barriers to entry for new companies, displacement of established technologies with new, innovative capabilities, and the overall buying power of the Federal Government.

- The procurement and acquisition practice of the DoD and the Federal Government are often convoluted, poorly communicated, and burdened with inertia that makes contracting with private industry far too difficult.

- As America confronts threats around the globe that are evolving at unprecedented speeds, we must find a way to better identify our defense needs, communicate them, and deliver them in a timely manner.

- The lack of responsive and rapidly scalable production capacity for consumable systems like Stinger and Javelin missiles highlights issues with our planning factors and manufacturing flexibility for long-lead items needed in short order, with little to no advanced warning.

- Finally, a highly skilled workforce is necessary for designing, engineering, and employing the game-changing technologies of the future. As we seek to keep pace with our strategic competitors, it is imperative that we invest in facilities, training, and education to support our defense industrial base workforce.

Sen Inhofe

- Today, the arsenal of democracy is a husk of its former self. While many companies still use equipment from the early Cold War, the weapons and equipment they manufacture have fundamentally changed, as has the workforce.

- We have far too many single points of failure. We have brittle supply chains. We have hundreds of production contracts at minimum sustaining rates. We have persistent funding shortfalls across the board, but particularly in our workforce development.

- In particular, our attempts to arm Ukraine have laid bare many of our vulnerabilities, from insufficient munitions stocks to slow production times and incredible bureaucratic hurdles, especially when it comes to doing business with allies and partners.

Ms. Lord

- In order for business to survive and flourish there must be a clear demand signal and a fast pace of predictable development, production, and sustainment.

- Technology innovation is now predominantly driven by the commercial sector, and DoD must accelerate its adoption of business practices that enable rapid testing and fielding of new capability.

- Many authorities that have been provided by recent NDAAs have been translated to policy and implementation guidance by the Department. These authorities need to be exercised so that the acquisition process moves at the speed of relevance.

- It requires leadership, from both Congress and DoD, to ensure that the DoD workforce embraces the imperative to conduct business in a manner that encourages patriotic individuals and companies to participate in our national security ecosystem, versus driving them away through frustration over slow decision-making and acquisition ambiguity.

- Appropriations must allow flexibility to adjust to technical innovations with reprogramming that meets our warfighting needs, not only of our nation but of our allies and partners. Disruptive market conditions, such as inflation, must be dealt with at the top-line budget level instead of slogging through the bureaucracy of each contract being adjusted by individual contracting officers at each geographic location.

- We should use the data published in the 13806 Industrial Base Report in 2018, to identify sole-source supplies of critical supply chain items to begin to build our supply chain resilience.

- It takes strong leadership to encourage the Department to use those to be able to move more quickly. So the tools are there, but I believe the leadership is required to hold the Department accountable for showing how they are using other transactional authorities, middle tier of acquisition and these other things.

- Begin to think about our releasability and exportability regulations. We have been very, very conservative with what we allow our closest allies to receive, in terms of technical information and manufacturing capability. We know that we do not have enough munitions. And we could look at countries like Australia that have capacity, that have throughput, that have the budget to develop indigenous capability, and work more closely with them to make sure we have the munitions we need and our allies and partners do as well.

- Congress has written law that allows DoD to go fast, and that has been translated into policy and implementation guidance, meaning there are procedures there. Where we have lagged is making sure that we actually train the acquisition workforce on how to use these and that we encourage what I call creative compliance.

- We have a very risk-averse workforce that is extremely concerned about media attention or congressional hearings pointing out when things did not go well. This is leading to a group that does not want to do anything other than what there is precedent for before.

- I think we need to give the entirety of the budgets for OTAs right up front and let people move fast. That is how the Defense Innovation Unit does, and they have been able to work very well with commercial entities.

- The biggest concern there is that manufacturing contracts are not being handed out quickly enough. We have a long process of going through CRADAs, some very small, small business contracts. But we just need to get out there and start putting things on contract. We can do that through the middle tier of acquisition as well as using OTAs.

- So middle tier of acquisition, for instance, just to explain that, says if you have a commercial capability or a fielded military system, that just through an incremental investment could really give us a step function change in capability, then we do not have to go through the Joint Staff’s requirements process that can take up to 2 years. What we can do is get the leaders of military services, the Secretaries, or the leaders of agencies to document that they do have that requirement, and then we can move out on middle tier of acquisition very quickly.

- COCOMs do not have acquisition authority. They generate the demand signal. So I think a better-informed COCOM can go and speak to a service and ask specifically for what they need and how to go about and get it, and that gets back to the issue of training the workforce. And I think that is one area where the committee could help by asking the Department what they are doing to train the workforce and what they are doing in terms of keeping metrics to look at the utilization of MTAs and how that has helped to rapidly field.

- There is a huge overlap (in incentivizing industry vs overcoming hurdles with the acquisition bureaucracy) – How often does this committee have a hearing calling out and trying to understand all the fantastic opportunities of OTAs and MTA, what that did to speed up the acquisition process, what that did to help the user downrange? We need to communicate the art of the possible and then encourage it, versus admiring the problem.

Mr. Berteau

- Industry’s ability to provide defense-unique goods and services depends entirely on DoD demand. For large parts of the defense industrial base, DoD is the largest—and sometimes the only—customer.

- When that is the case, the size and economic viability of the industrial base will be determined by how much DoD buys.

- Recently, DoD issued a report, entitled: “State of Competition within the Defense Industrial Base,” in response to Executive Order 14036: Promoting Competition in the American Economy. The report criticized defense industry for excessive consolidation but failed to acknowledge the department’s own role in that consolidation. For example, the report noted that only 3 prime contractors produce tactical missiles in the U.S. today but failed to note that DoD does not buy enough missiles to keep more companies in business.

- Government contracting is among the most highly structured and controlled elements of the U.S. economy. It consistently prioritizes compliance more than it rewards results. The contracting process is managed by people who often are unconnected to the benefits from the goods and services delivered by contractors. For example, contracting officers (and other officials) are evaluated by the percentage of contract dollars that are awarded to small businesses, but they are not scored on how well those companies actually perform on the contracts they receive.

- Government rules generally dictate payment for work only as or after it is completed. Companies have to fund themselves in advance of government invoice payments, and to obtain those funds, they must provide a competitive rate of return.

- The success of contractors depends on their ability to predict the future needs of DoD, to invest resources in being ready to meet those needs when contract bids are solicited, and to maintain the commitments in those bids for the months (or years) that it takes DoD to award the contract.

- Another measure of the DIB is the number of companies that participate as prime contractors or subcontractors. A recent report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies cited the drop in overall numbers of companies with one or more prime contracts from DoD, from more than 60,000 in 2009 to roughly 41,000 in 2020.

- The vast majority of those companies (more than 25,000 in 2020) are small businesses, and their contracts are frequently awarded through various programs that “set aside” awards only for eligible small businesses. This does help keep small businesses going, until they outgrow their eligibility for those “set-aside” contracts. PSC analysis shows that once such companies “graduate” from small-business status, their success in winning DoD contracts drops precipitously. In other words, DoD and federal small business policies and practices punish growth rather than rewarding it.

- Neither DoD nor any other agency tracks the number of subcontractors. DoD estimated in 2019 that up to 300,000 companies performed subcontract work for DoD in areas that would be covered by cybersecurity requirements. No one knows whether or to what extent the companies that no longer receive prime contracts are still in the defense industrial base as subcontractors. Efforts to increase supply chain resiliency will rely on layers of subcontractors, yet DoD knows little about these companies and even less about what makes doing business with DoD more attractive.

- Service contracts are often so competitive that margins for successful bidders are in the low single digits. A company that realizes a 4% or 5% fee on a contract simply cannot absorb the wage cost growth of 8% or 10% that we are seeing today.

- Half of DoD contract dollars go to services, and what was once a product is often now procured as a service. From data storage to satellite launches, DoD does not need ownership to benefit. This $200+ billion services market offers unrealized potential for DoD. For example, 70 percent of DoD system costs are in life-cycle support, sustainment and operations, yet there are too few opportunities for real competition.

- There are two things, I think, in addition to speed, although speed is vital here in today’s environment. One is to focus on results and outcomes rather than inputs. So much of our acquisition process is only focused on inputs — labor categories, labor hours, costs from the front end — rather than are you going to get the results you need. The second thing is in addition to focusing on outcomes is to, in fact, encourage people to take risks, and actually not punish them when they have gambled a little bit.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are those of the authors only and do not represent the positions of the MITRE Corporation or its sponsors.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter