Disrupting Acquisition Blog

Shorten MDAP Lifespans To Optimize Long-Term Success

DoD should cut planned operational lifespans for major weapon systems in half or shorter.

The average DoD aircraft is 30 years old. Most DoD ships, submarines, and satellites were launched last century. DoD and Congress struggle to adequately fund research, development, and production of new systems while also maintaining outdated legacy systems operating at a high OPSTEMPO. The ongoing tension of balancing readiness for today vs modernization for tomorrow is a big challenge for DoD.

What if DoD adopted a strategy whereby after 10 years of operational life,

it sells major weapon systems to Allied or partner nations?

This would enable DoD and Industry to maintain a continual development and production of new systems leveraging the latest mature technologies and innovative solutions. A steady pipeline of research, development, and production contracts would regrow and expand the shrinking industrial base, fueling competition, capital investments, and innovation.

Warren Buffett shared a lesson with students about taking care of your mind and body:

“Let’s say that I offer to buy you the car of your dreams. You can pick out any car that you want, and then when you get out of class this afternoon, that car will be waiting for you at home. There’s just one catch: It’s the only car you’re ever going to get…in your entire life. Now, knowing that, how are you going to treat that car?”

DoD acquires major weapon systems for 30–50-year operational lifespans. In preparation for this, DoD spends years on rigorous requirements, analysis, technologies, contracts, designs, development, testing, and production. The result is often delivery of outdated technology or an ideal solution for the last war. The late industry and defense acquisition executive Dr. Jacques Gansler often joked: “The F-22 got its name because it took 22 years to deliver.” They do this because it’s the only system an operator will get … in their entire career.

DoD buys fewer types of major weapon systems and in fewer quantities. Former Lockheed Martin CEO Norm Augustine highlighted this issue in 2012 with Augustine’s Law XVI:

“In the year 2054, the entire defense budget will purchase just one aircraft. This aircraft will have to be shared by the Air Force and Navy 3-1/2 days each per week except for leap year, when it will be made available to the Marines for the extra day.”

Congress is aggressively criticizing the Navy’s shipbuilding plans that seeks to divest of legacy ships at a faster pace of new ship deliveries. They highlight how this runs counter to achieving a mythical number of ships and only widens the divide between projected sizes of China and U.S. fleets. The Air Force seeks to divest 240 aircraft (including older F-22s) to fund research and development of new systems.

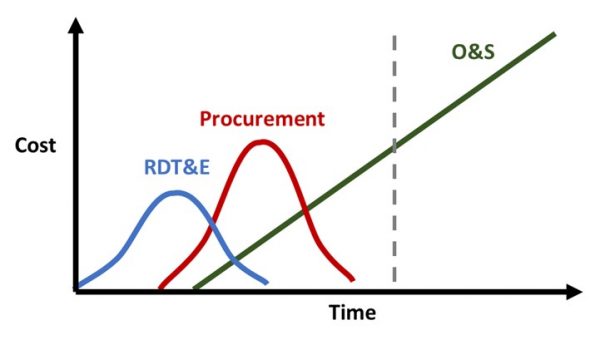

Anyone who has been around defense acquisition for some time has heard the adage that 70% of lifecycle costs occur in operations and sustainment. Your acquisition 101 class likely included the typical bell curve for research and development costs, followed by a larger curve for production, and finally an increasing line for operations and sustainment.

Anyone who has been around defense acquisition for some time has heard the adage that 70% of lifecycle costs occur in operations and sustainment. Your acquisition 101 class likely included the typical bell curve for research and development costs, followed by a larger curve for production, and finally an increasing line for operations and sustainment.

The more you use a system in operations, the more it will cost. This includes both a high operational cadence in any year and the number of years it is operational. As each year goes by, the costs to maintain and sustain a legacy system increases. Just like the dream car Warren Buffett bought you. The Air Force is spending over $10 billion to extend the F-22 service life and upgrade critical components.

If DoD cut a 30-year lifespan to 15 or even 10 years, that would be a major reduction in the system’s lifecycle costs to DoD. The break point will differ based on the type of system (e.g., aircraft, ship, ground vehicle, satellite, C4I) as each have different timelines and ratio of investment to O&S costs.

After a 10-year (or less) operational lifespan, the DoD and the prime contractor could sell it to an Allied or partner nation. Allies often don’t have the sizable defense budgets to acquire all the newest, exquisite major weapon systems, but these systems would offer a major upgrade over their current operational capabilities. It also allows a common suite of platforms and greater interoperability for Allied operations. They benefit from a lower purchase price and can operate the system for another 20+ years. The defense primes and industry benefit from the revenue to maintain and retrofit the transferred systems in addition to the new DoD business opportunities to sell advanced weapon systems. Alternatives to selling the systems to Allies or partners could be transferring them to lower priority Combatant Commands, the reserves, or other federal agencies.

Too many major system contracts today drive a winner take all approach. The winner dominates an industry segment for years while those who didn’t consider abandoning the market segment. This leads to lengthy protests or low-ball strategies like Boeing to undercut the market, often with negative impacts for DoD and industry. With fewer or no competitors remaining, the winning contractor leverages greater monopolistic bargaining power and reduces incentives to control costs, deliver on time, or fuel innovation.

The new paradigm would require each capability portfolio to maintain a roadmap of new systems and contract opportunities. It would integrate an enterprise strategy with the defense industry to include non-traditional contractors to maximize competition, strategic investments, and hot production lines. This includes expanding investments in the strained shipyards that can’t meet the Navy’s demands, ensuring we don’t spend years restarting of missile production lines, and awarding major production contracts to new, non-traditional defense companies. Contract strategies could also consider leasing opportunities to operate systems for a shorter timeframe before trading them in for the newer model.

The new paradigm would require each capability portfolio to maintain a roadmap of new systems and contract opportunities. It would integrate an enterprise strategy with the defense industry to include non-traditional contractors to maximize competition, strategic investments, and hot production lines. This includes expanding investments in the strained shipyards that can’t meet the Navy’s demands, ensuring we don’t spend years restarting of missile production lines, and awarding major production contracts to new, non-traditional defense companies. Contract strategies could also consider leasing opportunities to operate systems for a shorter timeframe before trading them in for the newer model.

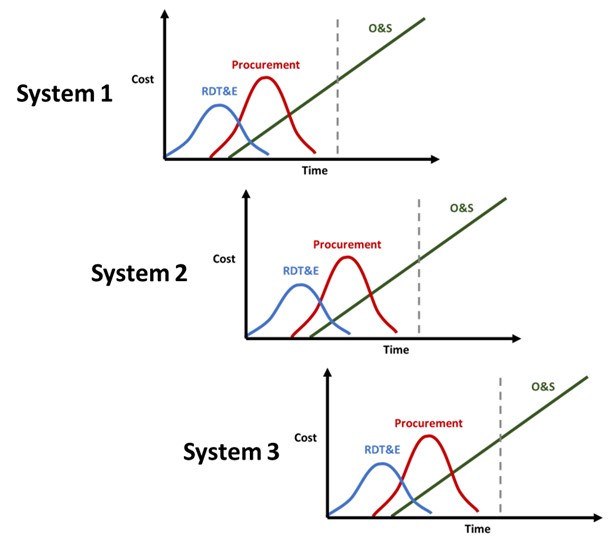

In addition to shorter operational lifespans, this new paradigm should aggressively shorten the development timelines. We can no longer afford to spend over a decade from idea to IOC. Pivoting to a more frequent cadence of system acquisitions enables greater opportunities for commercial acquisitions and exploiting new technologies across the Valley of Death. This is where industry can focus their research and development to produce mature systems to sell to DoD (and internationally). Industry operates at faster cycle times and can leapfrog each other in competitive markets than the traditional lengthy traditional acquisition model.

Enterprise portfolio analysis could shift the timelines of the subsequent systems left or right to find the optimal cadence based on costs (including capital investments), budgets, schedules, industry capacity, competitive strategies, supply chains, and other factors.

Pivoting to this new approach will take a concerted effort by DoD, Congress, and Industry.

What do you think of this approach?

- Will the cost savings of reduced O&S timelines fund the new modernization investments?

- Could the DoD get the proceeds of sales to Allies and partners put into an innovation or reinvestment fund?

- How will industry react from competition, strategic investments, and business models?

- What DoD enterprise processes (requirements, acquisition, contracting, budgeting, analysis) will need to transform to enable this new approach?

- How can this align with the pivot from individual programs to capability portfolios?

- Where are the opportunities to test this approach out? Autonomy?

- How can DoD align this with related commercial acquisition and PPBE reforms?

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are those of the authors only and do not represent the positions of the MITRE Corporation or its sponsors.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

0 Comments