Technology Maturity and Risk Reduction (TMRR) Phase

Agile Fundamentals Overview

Agile Glossary

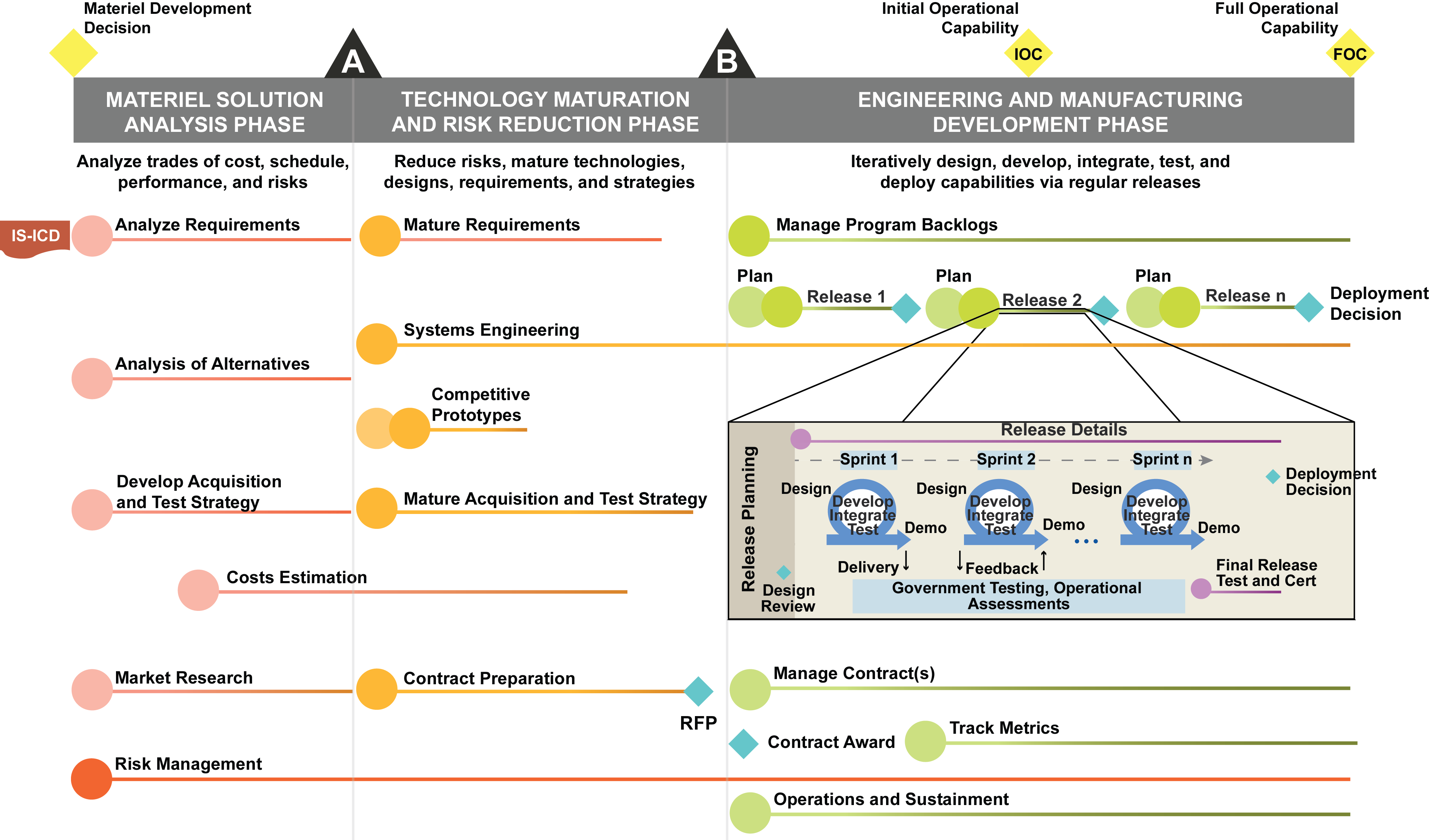

MATERIEL SOLUTION ANALYSIS (MSA) PHASE

Materiel Development Decision (MDD)

Analyze Requirements

Analysis of Alternatives (AoA)

Develop Acquisition Strategy

Market Research

Cost Estimation

Risk Management

TECHNOLOGY MATURITY AND RISK REDUCTION (TMRR) PHASE

Milestone A

Mature Requirements

Competitive Prototyping

Systems Engineering

Mature Acquisition Strategy

Contract Preparation

Risk Management

Request for Proposal

ENGINEERING & MANUFACTURING DEVELOPMENT (EMD) PHASE

Milestone B

Manage Program Backlogs

Release Execution

Manage Contracts

Metrics

Scaling Agile

Contract Preparation

Contracting is a challenging, but critical element in attaining the benefits of Agile practices. Upfront planning and preparation is required to properly issue a contract to acquire capabilities via Agile software development.

How is Contracting for Agile Different?

It is important to note that Agile is not a method of procurement, but a methodology that the contractor follows when developing software or capabilities. Contracting for Agile development should not be confused with rapid contracting, streamlined contracting, or agility in contracting, which differ from the form of contracting for Agile development discussed in this model.

Creating an effective contract is a challenging, but essential, element in attaining the benefits of Agile development practices. Long contracting timelines and costly change requests have become major hurdles in executing Agile developments and enabling small, frequent releases. Contracting strategies for Agile programs must be designed to support the short development and delivery timelines that Agile development requires. Today, a full and open competition for an IT contract can take as long as 12–18 months. Timelines such as these have driven many IT programs to structure programs in large, five-year increments, which in turn drive significant program risk. Understanding the true schedule drivers, constraints, and regulations for the contracting processes is critical to designing an optimal Agile acquisition strategy.

Contracting for Agile development has proven tremendously difficult not only for DoD but also for many other federal agencies. The current contracting environment is often incongruent with Agile development approaches. In many ways, the current environment is the opposite of what is needed to support contracting for Agile development. The July 2012 GAO Report on Effective Practices and Federal Challenges in Applying Agile Methods cites “Procurement practices may not support Agile Projects” as a key challenge area. Contracting for Agile development presents a unique challenge to the government not often encountered in the private sector because commercial firms usually rely on in-house staff to execute the Agile practices, whereas the government must obtain Agile development support through a contract arrangement. The table below identifies some of the key contracting areas where traditional contracting practices do not align to Agile contracting needs.

Current Contracting Environment Vs. Agile Contracting Needs

| Current Contracting Environment |

Contracting Area |

Agile Contracting Needs |

| Long contracting timelines often become the driver for program execution. |

Timelines |

Contracting is executed to support short development and delivery timelines. |

| The functional requirements are locked in at contract award; changes often require costly contract modifications. |

Scope |

Contracts allow the program to refine Agile requirements throughout the development process. |

| In most cases, the contractor executes the technical solution and reports progress to the government on a periodic basis; the government predominantly executes an oversight role. |

Government- Contractor Relationship |

The government and contractor work together on the development with daily interaction and collaboration; government and contractor act as partners. |

| Contracting support often physically resides in another location; as a result, contract personnel cannot provide consistent support and rapid turnaround on contract actions. |

Contracting Support |

Contracting support is physically co-located with the program to enable efficient execution of contract actions and provide day-to-day business advisory support. |

| The offeror proposes the development methodology and the contract is awarded based on the strength of the technical solution. |

Technical Evaluation |

The government states the desire to pursue an Agile development process and the contract is awarded based on strength of the development team and the vendor’s experience with Agile. |

Traditional IT acquisition programs contract with a defense firm to deliver an end-product capability based on a defined set of requirements. A services contract is based on the consistent delivery of contractor labor hours vs. a defined product. By using a services-based contract in an Agile environment the government can acquire the time and expertise of a contractor team of developers, testers, integrators, database specialists, etc. If using an existing contract vehicle (preferably a portfolio-level contract) the government can issue an order for each 6-month release based on the estimate of the requirements captured in the product backlog. During the release, the Agile requirements will likely change based on re-prioritization and changes in the development process. In contrast to a traditional product- or completion-based contract, a services contract provides the flexibility to change the release requirements continuously and still retain a consistent contractor team.

Contracting Business Environment

Agile contracting processes must be deliberate and well executed to enable the program to meet regular program delivery timelines. Contracting strategies, processes, and culture must create a business environment that supports small, frequent releases and responds to change. The small, empowered teams central to Agile call for a tight partnership across program managers, users, and contractors in the DoD environment. The government contracting community serves as an invaluable linchpin to establish this relationship in a collaborative, flexible business environment. Dedicated onsite contracting support fosters this close partnership with the program team. The program manager should work closely with the contracting officer as a business partner to devise a contract strategy. The contracting officer or the contracting officer’s representative (COR) in turn works with the release team to plan and manage upcoming contract actions, ensure compliance with contract requirements, and manage contractor performance.

The government program office and the Agile contractor development team must have a strong relationship characterized by daily interaction, frequent collaboration, and trusted partnership. In addition to executing the day-to-day development tasks, the government relies on the expertise of the contractor development team to help prioritize requirements, estimate the coverage and timing of future sprints and releases, and continuously evaluate and improve deployed capabilities. The contracting officer must work with the program office to foster this collaborative environment with the contractor.

Developing an Agile Contract Strategy

The contracting officer and program office involved in an Agile development process must understand the important distinction between contract requirements and the functional requirements. In many cases, the two types of requirements differ, which can lead to dangerous miscommunication between the contracting officer and program staff. Contract requirements are strictly limited to the tasks and activities the government requires a contractor to perform, which in many cases have only a distant and indirect relationship to the functional requirements managed and tracked in the product backlog (e.g., user stories). For example, the contract requirements may refer to staffing required for the development team (e.g., six full-time-equivalent software development staff) rather than to the functional requirements expressed in user stories (e.g., content search capability).

There is no single recommended contracting path or strategy for an Agile implementation, but establishing an environment with contract flexibility is essential to success. Several factors drive the choice of a specific contracting strategy. The program must understand the operational and programmatic priorities, constraints, and considerations involved in Agile development to develop an appropriate contract strategy. For example, deciding who will be responsible for primary system integration will determine whether the government can pursue a services versus a completion or product-delivery contract. A short development cycle often has more predictable requirements that may allow for a fixed-price contract. Long development cycles involve greater unknowns and may require a more flexible contract type. The political environment may favor a specific contract type or contract vehicle. The program should work closely with the contracting officer to consider the following factors when developing the contract strategy:

- Who is responsible for system integration?

- What type of support is needed beyond development support (e.g., testing)?

- What is the overall development timeline?

- What are the frequency of releases?

- Does the current political environment drive the use of a particular contract type or vehicle?

- What is the level of contracting support required?

- Is dedicated contracting support available to support multiple contract actions?

- Does the contracting office have a process that enables rapid execution of contracts?

- Are government resources available to actively manage contractor support?

- Is the program considered high risk?

- What level of risk is the government willing to accept?

- What level of integration is required?

- What is the level of integration risk if multiple contractors conduct parallel developments?

- Did market research identify available qualified contractors with Agile and domain experience?

- Is an Agile process well defined or already in place within the government program office?

- Are other, similar programs currently using or thinking of pursuing Agile?

- Does the program have executive-level support for Agile development?

- Can the program leverage existing contract vehicles – at the portfolio, enterprise, or external level?

Services Contracts

As noted, the Agile development process is characterized by constant change and reprioritization of requirements. To avoid a situation in which the contract scope must continuously change as well, programs should not select an Agile development contractor using a contract type that locks in requirements up front and defines end-state products on a completion-basis. Traditionally, IT development contracts are often product-based deliverable- or completion-type contracts that hold the contractor accountable for delivery of a product or capability. Under a completion contract, the contractor proposes a development methodology to the government and the government awards the contract based on the strength of the technical solution. Any change to the original requirements can trigger a potentially expensive and time-consuming engineering change proposal (ECP).

Alternatively, the government can consider using a services-based or level-of-effort/term-type contract to obtain Agile development support. Under this scenario, the government seeks the time and expertise of an Agile software development contractor, rather than a fixed end-product. The government chooses the contractor based on the strength and qualifications of the proposed development team rather than the strength of the technical solution. However, as with any services-type level-of-effort contract, this creates a risk because the contractor cannot be held accountable for the ultimate delivery of a completed product or deliverable. The government can only hold the contractor accountable for providing the time and expertise agreed to in the contract; the government is ultimately responsible for ensuring product delivery. The daily interaction between the government and contractor that is fundamental to an Agile development strategy should help to mitigate risks of non-delivery. The government-led development team should actively manage the development cycle and scale back capabilities when needed to meet the time-boxed sprint and release schedule. On the other hand, the team must carefully balance the need to meet schedule requirements against the risk of accumulating a high technical debt, which is the tendency to defer technical requirements to subsequent releases and sprints.

In addition, when using a services-based or level of effort/term-type contract, the government should carefully consider taking-on the role as the prime systems integrator. The government as the prime systems integrator assumes greater responsibility for the development process. An Agile development contractor can provide expertise and integration support to the government, but under a services contract the government is ultimately responsible for delivery (the contractor can only be held accountable for the delivery of the hours and support agreed to in the contract, not the end-item deliverable). When the government program has decided to pursue an Agile development approach, it should make a full commitment that includes increasing its responsibility and risk. In exchange, the Agile development process provides better assurance that the capabilities delivered meet user needs, which should be the ultimate measure of success.

“This is all about asking the program manager and the contracting officer to take a higher workload and more risk in exchange for the greater good.“ – John Inman, Contracting Officer for US CIS

The table below identifies some of the contract types available for a services-based contract strategy and the advantages and disadvantages that the program office should weigh.

Contract Type Comparison for Services Contracts

| Contract Type | Pros | Cons |

| Fixed-Price Services Contract (either FFP, or Fixed Price Level-of-Effort) |

|

|

| Cost Reimbursement Term (Level of Effort) Contract |

|

|

| Time-and-Material (T&M) (Labor Hour) Services Contract |

|

|

The commercial sector often uses T&M contracts for Agile development. Although T&M is the least preferred contract type in the government because the contractor has the least incentive to control costs, programs should consider this option if the government can manage the costs and scope on a proactive, continuous, and frequent basis. At the beginning of a project – a stage with many unknowns – T&M can provide maximum flexibility. Since the Agile development strategy requires daily interaction between the government and contractor staff, the controls needed to monitor contractor performance are built into the Agile development process and may provide the proper oversight to ensure efficient delivery and effective cost containment under a T&M arrangement. Structuring the program and task orders into smaller, frequent releases (e.g., six months) limits the risks often associated with a T&M contract because of the short period of performance and the “build to budget” development cycle. As the project continues down the development path, and the team better understands the requirements and establishes a rhythm, the contract type could shift to a fixed-price or cost-plus arrangement.

Often the political environment or the availability of a given contract vehicle forces programs into an associated contract type. If a T&M contract is not feasible or not preferred, programs can also consider a fixed price or cost reimbursement term contract. The program should work closely with the Agile cost estimators and engineering team to assess the level of effort involved in establishing the ceiling price (or fixed price) on the contract. This is especially important under a cost-plus-fixed-fee contract, where the fixed fee is based on a percentage of the contract ceiling at the time of award. In addition, under a fixed price contract, the government should establish deliverables (e.g., monthly report) to provide recurring

When utilizing a services-contract, it is important that the government identify the labor categories that will be needed to support the Agile development effort. 18F identifies the following Agile software development labor categories that offer a good starting point for government software development contract planning purposes.

- Agile Coach

- Backend Web Developer

- Business Analyst

- Delivery Manager

- DevOps Engineer

- Digital Performance Analyst

- Frontend Web Developer

- Interaction Designer / User Researcher / Usability Tester

- Product Owner

- Security Engineer

- Technical Architect

- Visual Designer

- Writer / Content Designer / Content Strategist

Contract Incentives

Under an Agile development, the team should focus 100% on delivery and speedy and efficient contracting processes to support short delivery cycles. Thus, the use of complicated contract incentive structures (e.g., incentive fees, award fees) is not recommended when using a services-type contract for Agile development. Not only are these types of incentives time-consuming and resource-intensive to administer, but under a services contract the government drives the process, schedule, and requirements. As a result, creating an incentive for “early delivery” or “cost savings” may not be achievable because the contractor is not in a position to control these outcomes. In this case, the government program is either setting up the contractor for “easy money” or is setting itself up for a contentious “blame game” battle with the contractor. Contract incentives can thus undermine a close working relationship between the government and contractor. Quick contract turnaround and a partnership between government and contractor are absolutely critical under an Agile development; contract incentives can become a distraction to the program, impeding the delivery cycle.

Contract incentives are often used when the government does not have the capacity or control to actively monitor contractor performance. However, under an Agile development, the government interacts with the contractor daily. The controls needed to manage contractor performance are inherent to the Agile development process. The frequent communication and collaborative spirit that is integral to the Agile process can make incentive contracts burdensome, unnecessary, and confrontational.

The program should still consider using a performance-based contract when contracting for services. The program can issue a Performance Work Statement and use past performance as an incentive/disincentive, or use metrics to manage contractor performance.

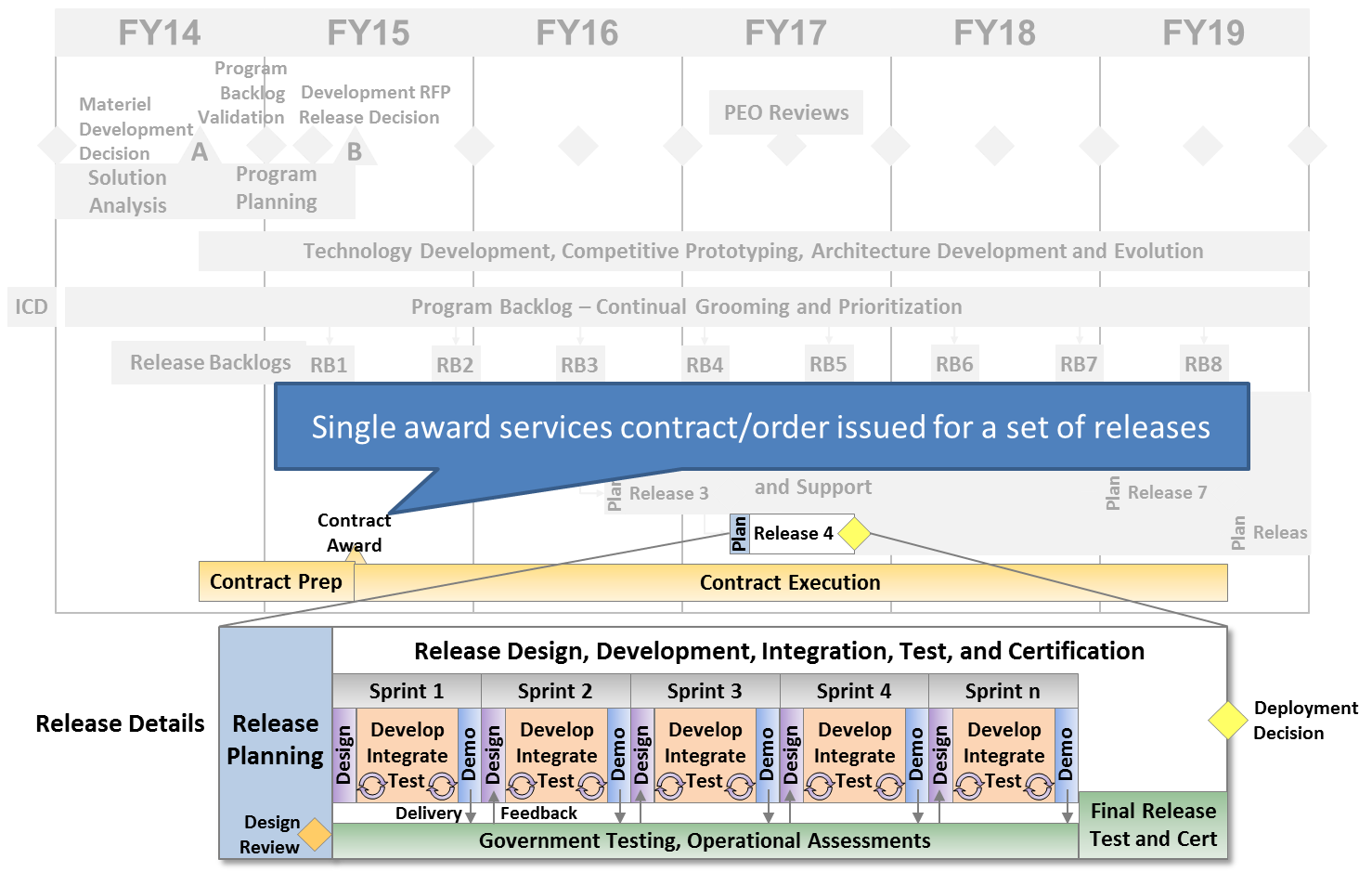

Services Contract Illustration

If a program is seeking to acquire the skills and expertise of a developer to participate in a government-led Agile development strategy, the government should use a services type contract. This is especially important if the program is seeking a consistent level of support from a single vendor across a series of sprints/releases. The program can pursue a separate stand-alone contract for Agile support services (which can take significant time to put in place), or it may consider leveraging an existing contract vehicle such as GWACS or GSA Schedules to acquire Agile support services on a task order basis or under a BPA. As illustrated below, a services contract awarded to a single-vendor assures the program of consistent support throughout the development of several release cycles.

Completion-Based Product Contracts

The government traditionally uses completion contracts for IT acquisition (specifying an end-product deliverable), but these are not necessarily the most appropriate or easiest to use for an Agile development. A completion contract requires upfront definition of requirements so that the contractor can adequately estimate the effort involved and then prepare and submit technical and cost proposals for the work. The nature of Agile makes it very difficult to to describe requirements at the level of detail necessary to create a cost proposal estimate (link to cost section). In addition, under a completion-type contract, the government should not direct the contractor to use an Agile development methodology. The government should use a Statement of Objectives (SOO) to describe the overall objectives of the program (e.g., capability delivery every 6 weeks) and let the contractor propose a development methodology that best meets the government’s objectives. It is harder to hold the contractor accountable for delivery if the government directs the contractor to use a specific development methodology.

If the program cannot use a services-type contract, one possible alternative would be to establish or use an existing single-award IDIQ contract and issue an order for each well-defined release or sprint. However, sprints typically have very short timelines that make it impractical to issue a new order for every sprint. Releases cover longer timelines, but often do not have defined scopes and requirements; changes made to the release requirements after contract award may trigger the need for an engineering change proposal. If considering the use of a non-services type contract, to the government could include a provision in the contract called a “no-cost change” whereby the government and contractor agree that requirements can be switched out on a one-for-one basis if the change does not result in an overall change to the contract price. This type of contract modification should not require extensive or time-consuming contract negotiation; it resembles the way the government treats a no-cost extension). This reduces contract administration burden, as well as providing some flexibility around requirements to preserve the nature of the Agile development process.

Using this type of vehicle effectively calls for significant coordination with the contracting office, as well as streamlined processes to rapidly issue orders that keep pace with the Agile delivery cycle. This strategy also requires more time and resources to award the initial umbrella contract vehicle and manage the contract and orders.

Programs could consider CPFF completion, FFP, or a fixed price incentive fee (FPIF) contract under this scenario. DoD promotes the use of FPIF contracts under Better Buying Power. FPIF incentivizes the development contractor to deliver the release or sprint below the target cost to obtain a higher fee per the negotiated profit adjustment formula. FPIF contracts also require the government to have a more in-depth understanding of the requirements, development work required, and estimated costs to effectively negotiate the fixed price. However, such contracts are more difficult to manage because the government must negotiate the target cost, target profit, ceiling price, and project adjustment formula with each order. Further, as is the case with any completion type contract, frequent changes and reprioritization of requirements may significantly change the end product, driving the need for an engineering change proposal and contract modification.

If using a completion-type contract that requires a specific product deliverable, establishing the product vision and incorporating it into the SOO or PWS is very important. The product vision is a high-level definition of the scope of the project. To establish the product vision, the government should ask the following questions:

- Who will use/buy the product? Who is the target customer?

- Which customer needs will the product address?

- Which product attributes are critical to satisfy the needs identified?

- How does the product compare against existing products. What are the unique needs?

- What is the target timeframe and budget to develop and launch the product?

The format for establishing the product vision according to the TECHFAR is as follows:

- For (Target Customer)

- Who (Statement of the need or opportunity)

- The (product name) is a (product category)

- That (key benefit, compelling reason to buy)

- Unlike (primary competitive alternative)

- Our Product (statement of primary differentiation)

A product vision is broken into manageable pieces of work that deliver incremental functionality. For example, if the product vision is to develop an online acquisition knowledge tool, the product vision can be broken into increments such as build platform infrastructure, enable collaboration capabilities, build resource library, etc., Each increment can be broken-out at the sprint-level, release-level, or any other level of capability that the government can use to define a product-oriented contract; however, the smaller or lower level the definition of a capability (e.g., sprint), the higher number of contract actions will be required to contract for each increment of capability.

Contracting for Outsourced Testing

Outsourcing testing for Agile requires special considerations because Agile testing can be significantly different than traditional testing. The acquisition strategy must reflect these differences for an outsourced Agile testing team to succeed.

When it comes to outsourcing testing contracts, there are several different areas that support can be contracted:

- Traditional consulting services for individual project-level services

- Staff augmentation

- Functional testing

- Integration testing

- Performance testing

- Testability assessment

- Quality assurance services that focus on the full lifecycle and cross-application dependencies

- Test management

- Test Center of Excellence

- Risk Based Testing

- Test Automation

- Agile Testing

- Test Data Management

- Quality management services that supplement quality assurance into strategic planning, targeting business outcomes based on a portfolio-approach

- Managed quality services

- Quality Center of Excellence

- On-site advisory/assessment

- Shared outcomes

- Quality assurance

The program should consider its comprehensive testing needs, as well as the needs of its governing portfolio or organization when outsourcing a test contract. It is very important to involve the testing organizations as part of the design and planning for a test contract, as well as for the primary development contract. Testing organizations are themselves service entities and need to provide information about the product that is under test and how the readiness for release will be measured and determined.

Contract Vehicles

The government has many pre-existing contract vehicles that it can use for Agile efforts. For example:

- Blanket Purchase Agreements (BPAs) off an existing General Services Administration (GSA) schedule contract (e.g., Schedule 70)

- Government-wide Acquisition Contracts (GWACs) (e.g., GSA Alliant, NITAAC)

- Agency-level multiple-award contracts (e.g., Encore II)

The government has already awarded such contracts, which makes them available for immediate use. However, these contracts have disadvantages such as limited selection of vendors with Agile experience, limitations on contract types, and non-dedicated contracting support staff.

Establishing a contract vehicle up front at the PEO, portfolio, or enterprise level would enable many programs to leverage the contract and the benefits of its streamlined processes, allowing them to focus their strategy and energy on task orders. The process leading to initial award of a competitive IDIQ vehicle can be lengthy; however, IDIQ contracts have the benefit that programs that fall under the scope of an enterprise IDIQ for Agile development can expedite the contracting process for individual task orders rather than replicating the full contracting process for every program-level contract.

At a basic level, there are a single-award IDIQ contracts (award to one vendor) and multiple-award IDIQ contracts. Under a multiple-award contract, several qualified vendors receive an IDIQ contract and all the contract awardees compete for each task order – a practice known as fair opportunity. The government can issue orders faster under a single-award IDIQ than under a multiple-award; however, a single award loses the benefits of continuous competition and the ability to switch easily among contractors in cases of unsatisfactory performance.

Contract vehicles suitable for Agile development have pre-established contract pricing, terms and conditions, and pre-vetted qualified vendor(s). This allows task orders to be issued in a matter of weeks versus months. A portfolio-level contract vehicle can have a targeted scope that should attract the right pool of vendors with Agile expertise in the technical domain. Programs can also set up a variety of portfolio contracts to meet other needs under an Agile development, such as obtaining contractor support in the areas of Agile subject matter expertise, independent testing, and continuous prototyping. However, these types of contracts require that the program invest time and resources up front to compete and award the umbrella contract vehicle.

Programs should also consider using GSA Schedule 70 when conducting market research for Agile development. Recently, 18F Consulting, partnering with the GSA Office of Integrated Technology Services, created an Agile BPA under the GSA Schedule 70 vehicle. It features vendors that specialize in Agile delivery services (e.g., user-centered design, Agile software development, and DevOps). To date, the Pool Three Full Stack, a contract for both design and development support has been awarded to 16 vendors that represent a mix of both large and small businesses. Currently, the BPA is only available to 18F (although 18F is a fee-for-service organization that can work with any federal agency). GSA has stated that it is working on a BPA that will be directly available to the rest of the federal government, allowing any federal agency to consider creating its own Agile BPA using the GSA Schedule 70.

When developing an IDIQ contract or BPA for Agile development, a program can consider several steps to streamline and improve the ordering process once the vehicle has been established. Orders under multiple award contracts are subject to fair opportunity under FAR Part 16.505. The FAR specifically states:

The contracting officer may exercise broad discretion in developing appropriate order placement procedures. The contracting officer should keep submission requirements to a minimum. Contracting officers may use streamlined procedures, including oral presentations.

The Contracting Officer is given broad discretion to develop procedures to streamline the issuance of orders under contracting vehicles; as long as they “afford all contractors responding to the notice a fair opportunity to submit an offer and have that offer fairly considered.” For task or delivery orders in excess of $5.5 million, the FAR requires the government to provide all awardees a fair opportunity to be considered, and a minimum of the following:

- A notice of the task or delivery order that includes a clear statement of the agency’s requirements;

- A reasonable response period;

- Disclosure of the significant factors and subfactors, including cost or price, that the agency expects to consider in evaluating proposals, and their relative importance;

- Where award is made on a best value basis, a written statement documenting the basis for award and the relative importance of quality and price or cost factors; and

- An opportunity for a postaward debriefing

The FAR specifically goes on to say that “normal evaluation plans or scoring of quotes or offers are not required.”

The government should take full advantage of the flexibilities offered under the FAR as it relates to issuing orders under fair opportunity provisions. Contracting for Agile development requires the ability to execute orders efficiently, effectively, and fairly. The following list identifies strategies that can be used to streamline the process to place orders under contract vehicles:

- Use oral proposals instead of paper proposals to reduce time and bid and proposal costs. To further streamline the use of oral proposals, the government can request vendors to submit secure YouTube videos as oral proposal submissions. The government evaluators can review the videos on their own time and reduce scheduling conflicts for the government evaluators

- Conduct group-based interviews with each Offeror team

- Use resume-only written evaluations with a video-based staffing plan proposal

- Conduct example-based evaluations such as submission of example artifacts from previous user stories and backlogs, and/or demonstration of successful products from previous projects

- Develop templates and standard business processes to streamline ordering procedures and ensure the quick execution of orders.

- Forge pre-agreements with the legal and policy offices on templates, formats, and processes that will enable efficient review cycles.

- Work with the contracting office to develop standard Performance Work Statement (PWS) language and proposal evaluation criteria.

- State in the base contract that IDIQ awardees must demonstrate positive past performance ratings on other task orders performed on the IDIQ to be eligible to receive future awards.

- Engage users and testers in developing the contract scope, evaluation criteria, incentives, and terms and conditions to ensure the contracting activity fully meets all needs and considerations.

- Understand the dedicated contracting process and associated timelines for executing task orders. Program managers should become familiar with contracting documentation and approval requirements.

Under FAR Part 16.505 also states that task orders issued under contract vehicles are not subject to protest, except for

- A protest on the grounds that the order increases the scope, period, or maximum value of the contract; or

- A protest of an order valued in excess of $10 million. Protests of orders in excess of $10 million may only be filed with the Government Accountability Office, in accordance with the procedures at 33.104.

- The authority to protest the placement of an order under (a)(10)(i)(B) of this section expires on September 30, 2016, for agencies other than DoD, NASA, and the Coast Guard (41 U.S.C. 4103(d) and 41 U.S.C. 4106(f)). The authority to protest the placement of an order under (a)(10)(i)(B) of this section does not expire for DoD, NASA, and the Coast Guard.

Key Questions to Validate Contract Strategies

- Do the contract strategy and timelines support frequent capability releases?

- Is the government the prime systems integrator?

- What level of risk is the government willing to assume?

- Are requirements relatively stable at the release level? Sprint level?

- Does the government want to drive the development process or does the government want the contractor to propose a development process?

- If pursuing a product contract, does the government have to dictate the use of Agile?

- Does the contracting environment support Agile development processes?

- Do existing contract vehicles support Agile delivery?

- What is the level of engagement between the contracting officer and the Agile team?

- What is the availability of the government to actively monitor the contractor’s performance on a frequent (e.g., daily) basis?

- Are there natural break-points in the development cycle where it would be feasible to change contractors with minimal disruption?

- Is it important to preserve continuous competition on the program?

For additional contracting information, refer to the Request for Proposal section.

- Contracting Cone, USD(A&S), Dec 2018

- GAO Report 12-681 Effective Practices and Federal Challenges in Applying Agile Methods, July 2012

- Going Agile: The new mind-set for procurement officials, Deloitte, May 2017

- Agile Contracts – PWS Templates, GSA Tech Guide

- Agile Contracts – Task Order Template, GSA Tech Guide

- Agile Contracts – Interview Questions for Agile roles, GSA Tech Guide

- Modular Contracting, 18F, Jan 2017

- DODI 5000.74 Defense Services Acquisition, Jan 2016

- OMB Contracting Guidance to Support Modular Development, Jun 2012

- Contracting for Agile Software Development in the DoD, Eileen Wrubel, Jon Gross, SEI, Aug 2015

- Agile Government Contracting, John Stenbeck, Kevin Jans

- Enabling Acquisition Success for Agile Development, Frank McNally, ASI Government, March 2014

- TechFAR Handbook

0 Comments