Understanding DoD

Understanding DoD Contracting

To get on contract with the DoD, it’s imperative that you understand the current DoD contracting culture, as well as DoD contracting strategies and terminology.

Current DoD Contracting Culture

Whether you are a first-timer or have worked with the DoD for years, DoD Contracting is like nothing else you’ll find in industry or academia. Nor will DoD Contracting look exactly like contracting with any other entity in the Federal Government, let alone state or local governments. Contracting even looks different between the Services so that the rules and formats for similar procurements with the Army and Air Force, for example, will be different enough to get you excluded for trying to use the format of one for the other.

In DoD Contracting, every procurement will be different—different timelines, different missions, different requirements, different funding types, different registrations and certifications, different proposal templates and instructions, different evaluation criteria, different entry points and innovation hubs, different Intellectual Property (IP) considerations, different regulations and policies. Some follow the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) and supplemental regulations and others ignore the FAR altogether and find their foundation in statute alone, such as Other Transactions. If you want a successful partnership with the DoD, you’ll need to understand these differences and abide by them in proposing and winning contracts, and then in delivering on those contracts.

If you want a successful partnership with the DoD, you’ll need to understand these differences and abide by them in proposing and winning contracts, and then in delivering on those contracts.

For as much as you may not understand DoD Contracting initially, your counterparts probably don’t understand you. Even if your Government Program Manager understands your technology, the Government team is unlikely to truly understand the complexities of running a business or what you must do to stay afloat, let alone be the successful technical unicorn they hope you’ll be, plus at a rock bottom price and giving away your IP. It’s unlikely that many of your counterparts have ever worked in private industry, understand your IP concerns or profit motive, can fathom why you’re wary of having a full-time employee doing nothing but writing hit-or-miss proposals, or can tell the difference in how a beginner small business views DoD opportunities versus how a tough-as-nails major defense contractor views DoD opportunities. Part of the relationship you build with your DoD partners may depend on you educating your counterparts, especially those who are open to learning.

Of all Federal Government contracting systems, DoD Contracting is one of the hardest to comprehend and dominate because it is heavily bureaucratic; your counterparts live in a culture that doesn’t normally focus on fast or innovative; the jargon is complex; and the time lines may be longer than your company can sustain while you wait for a steady flow of contracts to pay your bills. That last factor—lengthy timelines—may be harder than regulatory compliance and culture factors because your business model may not have the luxury of waiting out the slow and lumbering acquisition bureaucracy.

If these barriers sound like a problem, they are. The DoD knows it, too, and has begun to change, to reduce the restrictions, to experiment with new entry points, faster awards, statutory contracts, and briefer proposals—all in an effort to attract industry players with game-changing technologies that the US Government needs to stay ahead of adversaries like China and Russia. The DoD is actively looking at ways to lower the barriers to look more like what you might expect in working with non-Government investors so you’ll want to sell your product or service to the US Government instead of to a foreign adversary who will steal your trade secrets or copy your patent.

This change in bureaucratic culture won’t happen overnight, but you can take advantage of the new opportunities as the DoD creates new avenues for you to join the Defense innovation ecosystem.

Part of the relationship you build with your DoD partners may depend on you educating your counterparts, especially those who are open to learning.

Contracting Strategies and Terminology

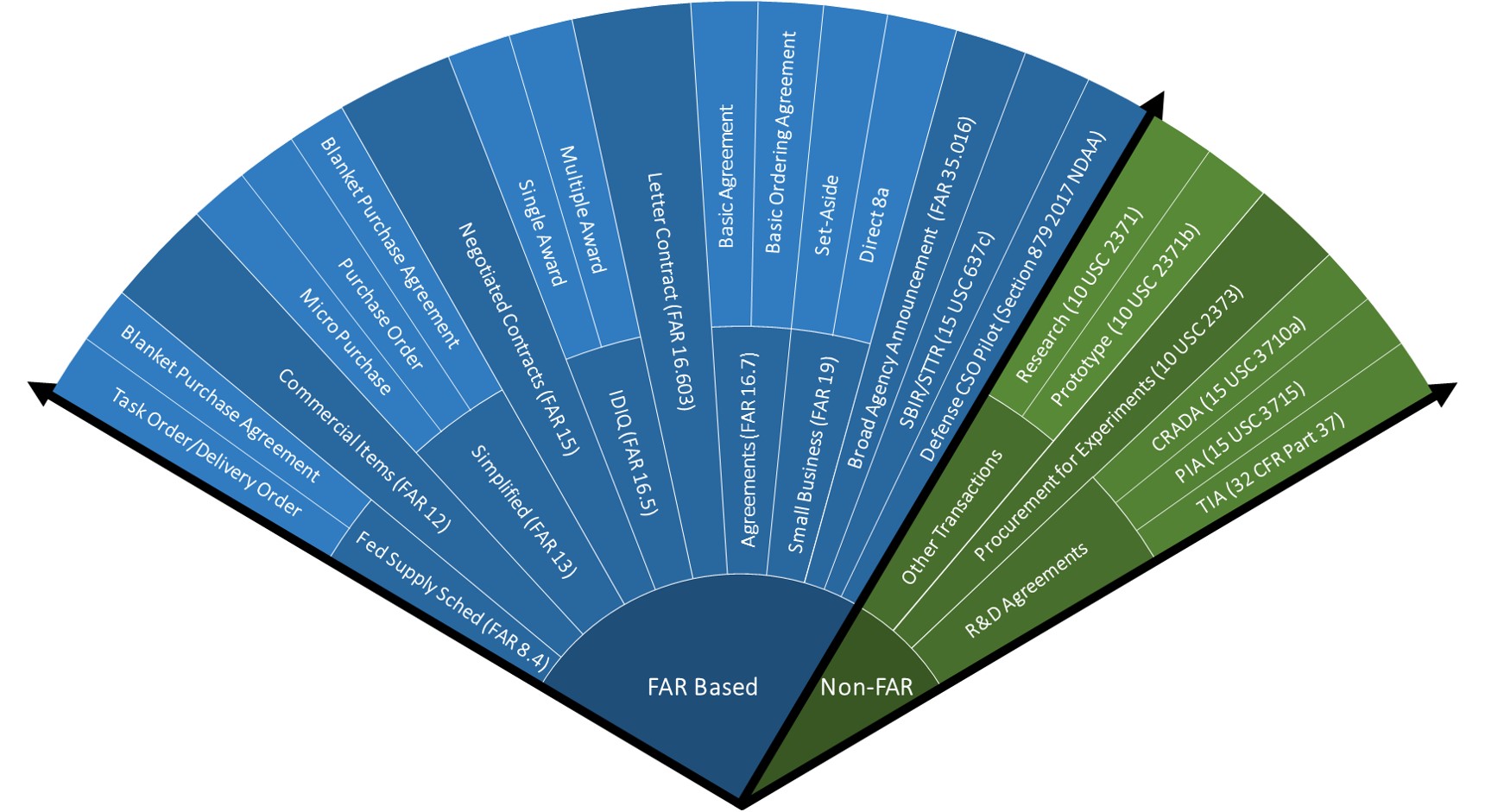

The Contracting Cone

The Contracting Cone is a clickable graphic that displays the options for contracting strategies, to include specific types of contracts or business arrangements and the solicitations that request proposals. Some of these terms can overlap and are misunderstood because of how both Government and industry use these terms.

For example, you may hear an innovation hub or a program manager refer to a “SBIR”–Small Business Innovation Research–as a solicitation, a contract, or a socio-economic program. All three usages can be correct in the right context. The SBIR program is a Government program designed to encourage small businesses to participate in innovative Research and Development with the intent to commercialize. Although the solicitation may be referred to as a “SBIR,” or possibly as a “SBIR topic,” the actual request for proposals may be a Broad Agency Announcement (BAA) or–new!–a Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO). The resultant contract or agreement is often called a “SBIR,” meaning that it’s awarded under the SBIR program. The agreement may be a contract, a purchase order, an Other Transaction for Research, or an Other Transaction for Prototype. The agreement could be written as a cost-type or a fixed-price-type arrangement. A SBIR solicitation can be a BAA or CSO but not all BAAs or CSOs will be released under the SBIR program. A SBIR could be awarded as an Other Transaction for Research or Prototype but not all Other Transactions will be awarded under the SBIR program.

Understanding these differences takes time and you may need to ask for the context–is this a solicitation? is this a contract? The Contracting Cone allows you to delve into different types of contracts and solicitations with a click and read through the pros/cons, references, applications, restrictions, frequently asked questions, or scenarios.

FAR-Based Contracts vs Statutory Agreements

The Contracting Cone is divided into “FAR based” and “Non-FAR.” FAR, or Federal Acquisition Regulations, are the better-known authorities for DoD contracts and solicitations, with the specific FAR citation listed with the title in the blue FAR blocks of the Cone. When a Contracting Officer references a “FAR-based contract,” they mean a contract under one of these authorities, subject to a plethora of regulations and pre-written, often pre-determined clauses.

“Non-FAR” points to statutory, rather than regulatory authorities. These are listed in the green blocks of the Cone, along with the corresponding statute. Non-FAR-based contracts, or statutory agreements such as Other Transactions, are less familiar but may be a better deal for a small business or startup because they don’t contain standard clauses and can be more freely structured. These agreements are generally simpler, more like business to business agreements, and less “bureaucratic” than contracts regulated by the FAR. They may have been around for decades but they have been relatively unknown and seldom used until around 2016-2018 when the DoD became more aggressive in courting industry.

Cost vs Fixed Price Contracts/Agreements

Both FAR-based contracts and statutory-based agreements can be cost-type or fixed-priced-type. Though there are variations of each, the ones you’ll most likely see on your early contracts with the DoD are Firm-Fixed-Price (FFP) and Cost-Plus-Fixed-Fee (CPFF).

FFP is typical of commercial products, R&D studies where you’ve written your own statement of work, and any product or service that can be defined well enough that you can price it. Under an FFP contract, the contractor assumes all the risk so if it costs you more than agreed to, you eat the loss. If you manage your costs well and have funds left over at the end of the contract, that’s profit for you.

Profit is the term used for fixed-price contracts whereas fee is the correct word for cost type contracts.

CPFF contracts put the risks of underestimating the costs on the Government. The DoD reimburses the allowable incurred costs and pays a fixed amount that is negotiated at the beginning of the contract. It may be negotiated as a percentage of the estimated costs but it is written into the contract as a precise amount, not a percentage. If you “overrun” the costs, your fee is the same, or fixed. You can be reimbursed for the overage of costs but you won’t receive additional fee unless the overage is a result of new work that has been added to the contract and was not anticipated in the original negotiation, such as an additional task that the DoD wants performed that you did not propose.

When you overrun a contract, you don’t receive an additional fee and cannot apply the original percentage on which you based the fixed fee to the cost growth or it would be deemed a Cost-Plus-Percentage-Cost contract, which, unlike in industry, is illegal for DoD contracts. Also, your contract will include a clause that requires you to notify the DoD in advance of spending all your funding, usually 60 days before you hit the 75% mark. This allows the DoD to decide to (1) recognize and fund an overrun (assuming funding is available); (2) terminate the contract; or (3) de-scope the work to the amount of funds available.

Two messy situations to avoid:

Situation 1

If you go over the funding provided on the contract, spending your own money in hopes of reimbursement, you are not guaranteed that the DoD will repay you.

However, if the Government receives a benefit from your service, you legally should be reimbursed, even if you didn’t comply with the contract and forgot to tell the Government that you were out of money while you kept working. If you incurred costs in the absence of funds (on the contract) and resort to legal action for reimbursement, it may be a long, drawn-out process for the Program Manager to find the correct funding, even if they agree that you should be paid. For this reason, and to maintain a good relationship with the Program Manager, many contractors accept the loss.

Situation 2

In the absence of funding–for whatever reason–the Government team should not encourage, beg, urge, cajole, plead, coax, demand, persuade, bully, threaten, direct, or any other synonym to convince you to work on your own dime.

You will probably never have a Contracting Officer tempt you to continue to work in the absence of funds because the Anti-Deficiency Act (ADA) has been drilled into them since their first day in the career field. However, other members of a DoD team probably have not been schooled as hard. Even knowing the ramifications, some team members will not stop a contractor from working on their own dime, and it does happen, particularly in emergency or urgent situations where the team member strongly feels the funds are imminent and it’s worth the risk. Because “knowing and willful” violations of ADA are a class E felony punishable by a $5K fine, up to two years imprisonment, or both, these team members usually look the other way or even ask not to be told. ADA violations and ratifications can become messy for both you and the DoD team, with publicity and at least a minimum of reprimands none of you want.

If you negotiate a cost type contract, you will need an accounting system approved by the DoD. A small percentage of the CPFF amount is held back until the contract close-out stage, which can take years to pass a final audit due to backlog. One trick some Contracting Officers allow so that they can close out the contract and the contractor can get their final payment faster is to convert a CPFF contract to FFP near the end when the contractor is certain they will have no additional costs to report and is willing to forgo any increase in overhead rates that might have increased since the original negotiation.

Statutory agreements such as Other Transactions can be of the cost or fixed price variety.

Contract type is determined by the Contracting Officer but if you follow the prescriptions in FAR Part 16, you may be able to convince the Contracting Officer to negotiate one you think is most appropriate to the risks. Even though FAR Part 16 doesn’t apply to Other Transactions, the language is still useful for supporting the type of Other Transaction that reflects the risk you are willing to take.

Colors of Money

When the DoD refer to “color of money,” they mean the categories of funding as appropriated by Congress for a specific purpose. Each category is considered a different “color,” though actual colors have nothing to do with it.

The five major pots of money are:

Military Personnel (MILPER): includes pay, allowances, subsistence, travel

Operations and Maintenance (O&M): includes support for operations, training/education, and maintenance

Research, Development, Test and Evaluation (RDT&E): for research and development

Procurement: for programs approved for production

Military Construction (MILCON): includes acquisition, construction of or installation of facilities such as schools, maintenance facilities, or weapon storage facilities.

The Five Major Pots (“Colors”) of Money

- Military Personnel (MILPER)

- Operations and Maintenance (O&M)

- Research, Development, Test and Evaluation (RDT&E)

- Procurement

- Military Construction (MILCON)

If you are new to working with the DoD, you’re most likely to be funded with RDT&E funding or O&M. The trick with colors of money is to make sure that the color is used for the purpose Congress meant it to be used for. This is fiscal law. If you are contracted to deliver an R&D study under the SBIR program, you would expect that the funding–and the wording in your contract–to match the purpose and the RDT&E pot of money. You would not expect to find Procurement funds for production on your SBIR Phase I contract. If you are providing a regularly updated app for training and education of troops, then you would expect that your contract wording and funding both match the O&M pot of money, not an obscure fund cite for improving or building facilities.

There are sub-differentiations of each color. Each category is given a numerical code according to whether it’s Air Force, Army, Navy, Marines, or DoD-wide. For example, RDT&E Air Force funding is called “3600” funding, sometimes called “two-year” funds because it can be obligated in the current and next fiscal year.

The correct color of money is the DoD’s responsibility, not yours, but it may affect exactly how a Statement of Work or Performance Work Statement is worded. The Contracting Officer and DoD’s legal counsel will be attuned to the color of money because using funding for something other than what it was intended for can be an ADA violation, as mentioned above.

Common Contract Strategies

All of the above considerations–FAR-based vs statutory, cost vs fixed price, color of money, etc.–factor into the contract strategy. If you’re new to the DoD, the following are the most likely strategies you’ll encounter:

Commercial Items

Supplies and services that meet the definition of a commercial item at FAR Part 2.1 may be acquired using the streamlined procedures set forth in FAR Part 12. Non-Developmental Item (NDI) and Commercial Off-the-Shelf (COTS) are considered subsets of commercial items.

DFARS Part 212.102(a)(iii) further expands the application of commercial item procedures to supplies and services from non-traditional defense contractors and, when appropriate, from business segments of traditional contractors that meet the definition of non-traditional defense contractor, for purposes of enhancing defense innovation and investment and encouraging nontraditional vendors to do business with the government. A commercial item determination is not required when commercial item procedures are applied to procure supplies and services from non-traditional defense contractors, nor does applying commercial item procedures for such procurements mean an item is commercial.

As defined in 10 U.S.C. §2302, a non-traditional defense contractor is an entity that is not currently performing and has not performed, for at least the one-year period preceding the solicitation of sources by the Department of Defense for the procurement or transaction, any contract or subcontract for the Department of Defense that is subject to full coverage under the cost accounting standards prescribed pursuant to Section 1502 of Title 41 and the regulations implementing such section.

Many entities will find they qualify as nontraditional defense contractors because:

- They are a small business exempt from CAS requirements

- They exclusively perform contracts under commercial procedures

- They exclusively perform under firm-fixed-price (FFP) contracts with adequate price competition

- They performed less than $50 million in CAS covered efforts during the preceding cost accounting period

Common Applications

- COTS Defense Business Systems

- COTS solutions and technologies

- Commercial products and services

- Products and services provided by non-traditional defense contractors

- Information Technology (IT) products and services

- Health IT services and solutions

- Cyber services and solutions

- Cloud services and solutions

- Software licenses

- Telecommunications and wireless services

- Mobile solutions

Restrictions

- Commercial item determination required

- Contract types limited to Firm-Fixed-Price (FFP), Fixed-Price with Economic Price Adjustment (FPEPA), and Time-and-Materials (T&M)

See additional references and resources for this strategy in the Contracting Cone – Commercial Items

SBIR/STTR Contracts

Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) is a competitive program that encourages small businesses to engage in Federal R&D with the potential for commercialization to stimulate innovation.

Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) is another program to facilitate cooperative R&D between small business concerns and non-profit U.S. research institutions with the potential for commercialization of innovative technological solutions.

Federal agencies with R&D budgets exceeding $100 million are required to allocate a percentage of their R&D budget to these programs. Participating agencies determine relevant R&D topics for their programs.

SBIR/STTR is a gated process with three phases executed through BAA contracts, grants, or agreements:

- Phase I Concept Development: Explore technical merit and feasibility of an idea or technology and determine the quality of performance of the small business prior to providing further Federal support in Phase II. Contracts are no more than six months in duration and are funded by the SBIR/STTR program. Typically, Phase I awards are typically less than $150,000.

- Phase II Prototype Development: Continue R&D efforts initiated in Phase I and evaluate commercialization potential. Contracts are no more than 24 months, are funded by the SBIR/STTR program, and typically are less than $1 million. Award amounts are based on Phase I results and scientific and technical merit for commercialization.

- Phase III Commercialization: Work that derives from, extends, or completes R&D efforts under prior SBIR/STTR Phase I/II and enables a small business to pursue commercialization. Phase III work may be for products (including test and evaluation), production contracts, and/or R&D activities. There is no limit on the number, duration, type, or dollar value of Phase III award. Phase III awards cannot be funded by the SBIR program. Agencies may enter into a Phase III SBIR contracts, grants, or agreements at any time (competitively or non-competitively) with a Phase I or Phase II awardee.

Non-FAR Based Application

Although agencies primarily use procurement contracts, grants, or agreements in the SBIR program, the use of Other Transactions (OTs) as award instruments is authorized. Section 863-864 of the FY18 NDAA includes express authority to allow for the award of Prototype OTs in the SBIR program.

Common Applications for SBIR Phase I and II

- R&D studies

- Prototypes

- Science & Technology (S&T) efforts

- Technology maturation

Common Applications for SBIR Phase III

- Solutions and technologies

- IT software and products

- R&D studies

- Prototypes

- S&T efforts

- Technology maturation

Restrictions

- SBIR/STTR data rights protection: Apply to all phases and restricts the Government from disclosing SBIR data outside the Government. Government cannot compete technologies containing SBIR data.

- Sole source Phase III awards may not be appropriate in all cases if multiple sources exist in the open market for similar product.

See additional references and resources for this strategy in the Contracting Cone –SBIR/STTR

Broad Agency Announcements (BAAs)

BAAs are used to obtain proposals for basic and applied research and development to advance or evaluate cutting edge technologies, not related to a specific system or hardware requirement. BAAs should be used when meaningful solutions can be expected. BAAs are typically “open” and proposals accepted for a specified period of time. Proposals submitted in response to BAAs may or may not lead to contracts.

BAAs may be used for the award of Science and Technology (S&T) proposals for the following:

- Basic research (budget activity 6.1)

- Applied research (budget activity 6.2)

- Advanced technology development (budget activity 6.3)

- Advanced component development and prototypes (budget activity 6.4)

BAAs may be used to award FAR-based contracts or non-FAR based agreements.

Common Applications

- Research & Development (R&D) studies

- Prototypes

- Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) efforts

- Science & Technology (S&T) initiatives

- Technology maturation

Restrictions

- Limited to basic and applied research

- Must be funded using RDT&E funds

- Cannot be used for specific system or hardware solution

- Cannot be used for systems engineering and advisory services

- Cannot be used for production

See additional references and resources for this strategy in the Contracting Cone – BAAs

Commercial Solutions Openings (CSOs)

The Defense Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO) Pilot is a competitive program authorized by Section 879 of the FY17 NDAA to obtain solutions or new capabilities that fulfill requirements, close capability gaps, or provide potential technological advances. CSO procedures are similar to those for Broad Agency Announcements (BAAs), with the exception that a CSO can be used to acquire innovative commercial items, technologies, or services that directly meet program requirements, whereas BAAs are restricted to basic and applied research. The CSO program may also be used to acquire R&D solutions from component development through operational systems development.

For CSO purposes, innovation is defined as any technology, process, or method, including research and development that is new as of the date of proposal submission or any application of a technology, process, or method that is new as of proposal submission.

Non-FAR Based Applications

CSO procedures are also used to award non-FAR based agreements. Specific limitations and requirements apply when using the CSO evaluation procedures and are dependent upon the non-FAR based strategy selected.

Common Applications

- Commercial products and services

- Information Technology (IT) product and services

- R&D studies for commercial technology

- Commercial Technology maturation

Restrictions

- Limited to fixed-price or fixed-price incentive contract arrangements

- Awards exceeding $100 million require approval from Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (USD A&S) or military service acquisition executive

- Requirement to promote competition in accordance with DFARS Part 215.371-2 does not apply

- Authority expires on September 30, 2022

See additional references and resources for this strategy in the Contracting Cone – CSOs

Other Transactions

Research OTs (10 U.S.C. §2371)

Research OTs are appropriate for basic, applied, and advanced research projects related to weapons systems or other military needs. Research OTs may be used to pursue research and development of technology with dual-use application (commercial and government). Unlike Prototype OTs, Research OTs do not include authority for transition to follow-on production contracts or transactions.

Research OTs should include a cost sharing arrangement that, to the maximum extent practicable, do not require funds provided by the government to exceed funds provided by other parties. There is latitude for the final share ratio to be other than 50/50 based on considerations such as the party’s resources, prior investments in the technology, commercial vs. military relevant, unusual performance risk, and nature of the project.

Although the Competition in Contracting Act (CICA) is not applicable, competition should be pursued to the maximum extent practicable to incentivize high quality and competitive pricing.

Research OTs are also used to execute Technology Investment Agreements (TIAs) when the government seeks to retain intellectual property rights that deviate from the Bayh-Dole Act (35 U.S.C. §18 and 37 CFR Part 401) which permits a university, small business, or non-profit institution to pursue ownership of an invention made using government provided funds.

Restrictions

- FAR/DFARS are not applicable

- 50/50 cost share arrangement to maximum extent practicable

- Agencies must be explicitly authorized by Congress to use OTs

- Contracting Officer must have Agreement Officer authority to execute

Prototype OTs (10 U.S.C. §2371b)

Prototype OTs are appropriate for research and development and prototyping activities to enhance mission effectiveness of military personnel and supporting platforms, systems, components, or materials. Prototype OTs may be used to acquire a reasonable number of prototypes to test in the field before making a decision to purchase in quantity. Prototype OTs provide a streamlined path to award a non-competitive follow-on Production OT or FAR contract.

For OTs, a “prototype project” is defined as a prototype project addressing a proof of concept, model, reverse engineering to address obsolescence, pilot, novel application of commercial technologies for defense purposes, agile development activity, creation, design, development, demonstration of technical or operational utility, or combinations of the foregoing. A process, including a business process,may be the subject of a prototype project.

Prototype OT Award Criteria

One of the following must be met to award a Prototype OT:

- At least one non-traditional defense contractor* participates to significant extent or

- All significant participants are small or non-traditional defense contractors or

- One third of total cost provided by sources other than gov (if no non-traditional defense contractor participation) or

- Agency Senior Procurement Executive determines circumstances justify use of a transaction that provides for

- Innovative business arrangements not feasible or appropriate under a contract

- Opportunity to expand defense supply base not practical or feasible under a contract

*As defined in 10 U.S.C. § 2302(9), a non-traditional defense contractor is an entity that is not currently performing and has not performed, for at least one-year period preceding the solicitation of sources for the other transaction, any contract or subcontract for the DoD that is subject to full coverage under the cost accounting standards (CAS).

Competition

Although CICA is not applicable to OTs, competition should be pursued to the maximum extent practicable to incentivize high quality and competitive pricing. Additionally, competitive procedures are required in order to leverage the authority for transition to follow-on production contracts or transactions without subsequent competition.

Restrictions

- FAR/DFARS are not applicable

- Contracting Officer must have Agreement Officer authority to execute OTs

- Cost sharing requirements apply if no significant participation by non-traditional defense contractors

- Limited to requirements that have a prototyping element

- OTs can only deliver limited quantities of prototypes

- Prototype project must address anticipated follow-on activities, competitive procedures must be used to award prototype project, and successful completion of prototype project required to transition to follow-production vehicle

- May not exceed $500M without Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Development (USD R&E) or USD A&S approval

See additional references and resources for this strategy in the Contracting Cone – Other Transactions.

Procurement for Experimental Purposes ("2373")

Procurement for Experimental Purposes (commonly referred to as “2373”) authorizes the government to acquire quantities necessary for experimentation, technical evaluation, assessment of operational utility, or to maintain a residual operational capability. This authority currently allows for acquisitions in the following nine areas:

| Ordinance | Signal | Chemical Activity |

| Transportation | Energy | Medical |

| Space-Flight | Aeronautical Supplies | Telecommunications |

2373 can be competitive or non-competitive and awarded using a contract or agreement. FAR and DFARS are not applicable, therefore, formal competitive procedures do not apply and any resultant contract is not required to include standard provisions and clauses required by procurement laws. Instead, a contract could be written using commercial terms. Another option is to leverage the authority of 10 U.S.C. §2371 or 10 U.S.C. §2371b and execute a research or prototype OT for the items allowed under this statute.

A Determination & Finding (D&F) identifying the following information is required to execute a 2373 award:

- A description of the item(s) to be purchased and dollar amount of purchase

- A description of the method of test/experimentation

- The quantity to be tested

- A definitive statement that use of the authority at 10 U.S.C. §2373 is determined to be appropriate for the acquisition

Restrictions

- FAR/DFARS N/A

- Secretary of Defense delegation required (currently delegated to Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), Navy, and selectively within Air Force and Army)

- Contracting Officer must have Agreement Officer authority to execute unless awarded as a FAR-based contract

- Purchases limited to quantities necessary for experimentation, technical evaluation, assessment of operational utility, or safety or to provide a residual operational capability

- Appropriate for use in select situations to prevent inappropriate use/abuse and potential revocation of authority

See additional references and resources for this strategy in the Contracting Cone – Procurement for Experimental Purposes.

CRADAs

Authorizes federal labs to enter into agreements with other federal agencies, state/local government, industry, non-profits, and universities for licensing agreements for lab developed inventions or Intellectual Property (IP) to commercialize products or processes originating in federal labs.

- Labs may seek an industry partner with resources to successfully market invention or commercialize

- Labs may seek an industry partner to stimulate a market for new technology

- Non-federal/industry partner may seek government lab to further develop unique resources

Common Applications

- Research Development & Demonstration (RD&D) collaboration and technology advancement efforts

Restrictions

- Limited to government owned or government owned, contractor operated labs

- Government may contribute wide variety of resources, but no funds

- Collaborating partner may contribute funds to the effort, as well as personnel, services and property

- May not provide for research that duplicates research being conducted under existing programs carried out by DoD

See additional references and resources for this strategy in the Contracting Cone –CRADAs

Other Relevant Topics

The DoD has greatly increased use of Other Transactions in recent years as a flexible business arrangement for prototyping and early technology development. DoD organizations can issue direct OT awards, or they may leverage one of many Other Transaction Consortia have formed around technology or mission areas.

The Air Force, in particular, has begun leveraging Pitch Day events for businesses to pitch solutions to address Air Force needs and opportunities with contracts awarded during the event.